From a private ballet academy to professional education

Twists and turns of the Finnish National Ballet 8

When the Finnish Opera had its first ballet performances in 1922, the opera company didn’t yet offer its own ballet education. Instead, dancers were mainly amateur students from the Helsinki Dance Institute and the dance schools of Elo Kuosmanen and Toivo Niskanen, who were both notable dancers and choreographers. Ballet education was also provided by teachers from St. Petersburg and Copenhagen. Most of the dancers in the early years of the Finnish Opera Ballet, for example Irja Aaltonen, Edith Wohlström and Arvo Martikainen, were educated at the Helsinki Dance Institute by Russian teachers who had fled the revolution. Some had also studied in St. Petersburg, such as Mary Paischeff, who danced the lead role of the first Swan Lake, and Senta Will, who debuted in Scheherazade in the same year.

Ballet education at the Finnish Opera

The story of the Ballet School of the Finnish National Opera and Ballet began in the first years of the Finnish Opera Ballet in the 1920s. The need for teaching was understood straight away, and the aim was to turn young ballet beginners into future stars for the company. Ballet master George Gé was in charge of the initial lessons, assisted by dancer Senta Will who had studied in St. Petersburg.

To start with, the Finnish Opera offered a paid-for, private dance academy run by dance artists. Anyone could enrol as a student. By the 1930s, there were six ballet classes, the top two of which offered professional training and the rest were preparatory classes from year one to four. Some of the students in the beginners’ class were very young, the youngest being just four years old. Boys and girls rehearsed together and each class had up to 30 students.

The first dancers educated at the academy started to perform in the late 1920s. Lucia Nifontova, for instance, debuted at the Finnish Opera Ballet in 1929. She had started her ballet education at Hilma Liiman’s ballet school and the Helsinki Dance Academy but continued her studies at the Finnish Opera, where her teachers included George Gé. Once Gé gave up his ballet master duties, the new ballet master Alexander Saxelin also took over responsibility for the ballet education.

In 1942 the Finnish Opera took formal ownership of the ballet school. This brought additional stability to the school’s operations, while the tuition fees meant extra income for the opera company. In 1952 the ballet master was relieved of tuition duties, and Kari Karnakoski was appointed specifically to head the ballet school. Later on, the ballet master or the deputy ballet master would again assume responsibility for the school.

A major change in the ballet school’s operations took place in 1956, when the Finnish Opera was granted a regular government subsidy. As tuition fees were no longer needed to cover the costs, they were abolished. Subsequently, the ballet school was transformed into a professional education institute with entrance exams and a systematic study path.

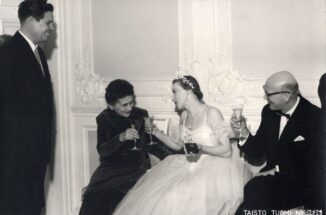

Marita Ståhlberg, who first started teaching alongside her work as a dancer in 1953, was one of many who built a long career at the ballet school. From 1972 to 1986, she served as the school’s director. Together with Sonja Tammela, Ståhlberg also created its first own large-scale production, The Blue Pearl, in 1961. Maj-Lis Rajala was another key character in the history of the ballet school. She worked as a teacher from 1969 and as the director from 1986, collaborating closely with her dancer colleague, artistic director of the ballet Doris Laine. The first dedicated boys’ class was established in 1960, headed by Uno Onkinen until 1974. The long-serving teachers of the 1970s and 1980s also included Saga Eriksson and Aku Ahjolinna.

Ilkka Lampi, a young graduate from the pedagogy department of the Leningrad Choreographic School, joined the ballet school as a teacher in the 1980s and was appointed as its director in 1993. He brought many new teaching ideas with him and renewed the curriculum. A ballet pre-school was established in 1984 for children from 6 to 9 years of age. With the new Opera House under construction, the ballet company needed more dancers, which meant taking more ballet students and recruiting more teachers. The number of students doubled from 1975 to 1994, when a total of 144 dancers were taught at the ballet school by 15 teachers.

When the new Opera House was completed in 1993, the most advanced classes moved to the new premises with the Finnish National Ballet. Most of the ballet school stayed at the old Opera House at the Alexander Theatre and continued to use the rehearsal facilities nearby.

Inclusion in the official education system

In 1998 the ballet school became part of the official education system of Finland and adopted its current name, Ballet School of the Finnish National Ballet. Students who had finished comprehensive school could apply to its upper secondary vocational education programme and complete a basic education in dance.

Students could complement the three-year vocational education with general studies and take their matriculation examination. They no longer had to qualify every year but were automatically allowed to complete the entire programme after passing the initial entrance exam. As the students would eventually graduate with a proper vocational qualification, they could also apply for student grants and loans.

The Ballet School of the Finnish National Ballet finally gave up its facilities at the Alexander Theatre in 2003 when new premises were completed at Taiteen talo (“The house of the arts”), an old bread factory in Sörnäinen, East Helsinki. To complement the Leipätehdas (”bread factory”) rehearsal halls, the facilities of the Opera House were used in the evenings. Close collaboration with the Finnish National Ballet also continued in Main Stage performances, where the youngest students of the Ballet School are regularly seen in child roles and vocational students sometimes dance side by side with the professionals of the Finnish National Ballet.

At the start of 2022 the Ballet School of the Finnish National Ballet moved all its operations to the Opera House, where large warehouse spaces were refurbished into new rehearsal halls, dressing rooms and break areas. Today the Ballet School teaches approximately 40 vocational students aged 16 to 18 and about 150 students aged 7 to 15 in basic arts education and ballet beginners’ classes.

Though in recent decades most of the headmasters of the Ballet School have been recruited from outside the Finnish National Ballet, they have worked closely together with the deputy headmaster or education coordinator, who has had a background in ballet and has taken a central role in planning the curriculum. Since the 2010s, the education coordinator post has been held by a dancer of the Finnish National Ballet.

Text JUSSI ILTANEN

Photos THE ARCHIVES OF THE FINNISH NATIONAL OPERA AND BALLET (i. al. Tenhovaara, Finlandia-kuva, Kari Hakli, Krista Keltanen, Mirka Kleemola)

Further reading

Niiranen ym. (toim.): Balettioppilaitos – sata vuotta suomalaista balettikoulutusta (Siltala 2021)

Laakkonen ym. (toim.): Se alkoi joutsenesta. Sata vuotta arkea ja unelmia Kansallisbaletissa (Karisto 2021)

Irma Vienola-Lindfors & Raoul af Hällström: Suomen Kansallisbaletti 1922–1972 (Fazer 1981)

Other sources

The Archive of the Finnish National opera and ballet

Kansan Kuvalehti 7/1930

Naamio, aikakauslehti näyttämötaiteita varten 1/1932

Recommended for you

The Finnish Opera establishes a ballet company

Gé, Saxelin, Gé, Saxelin…

Tours for soldiers and sad news from the front

Summer tours and films bring ballet to the entire nation

International stars from the east and west

Ballet masters change, Sylvestersson remains

The Finnish National Ballet as an ambassador for Finland