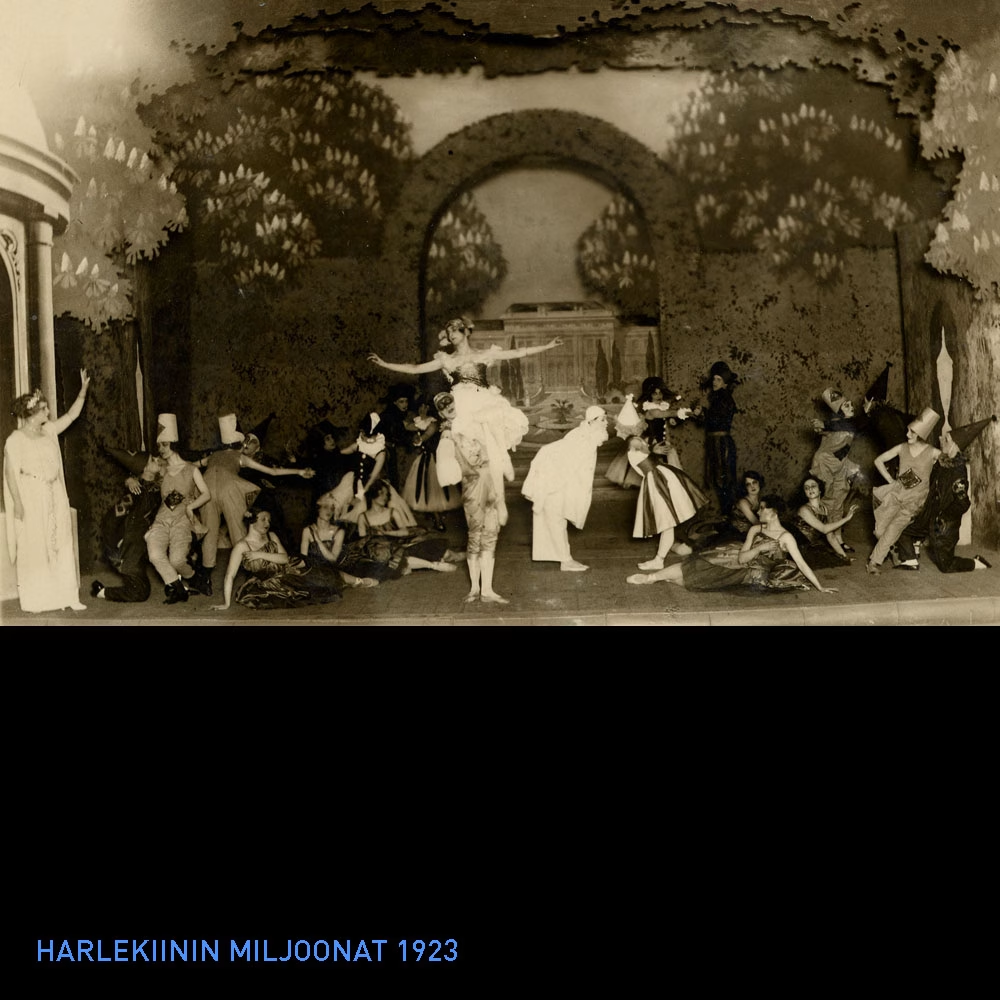

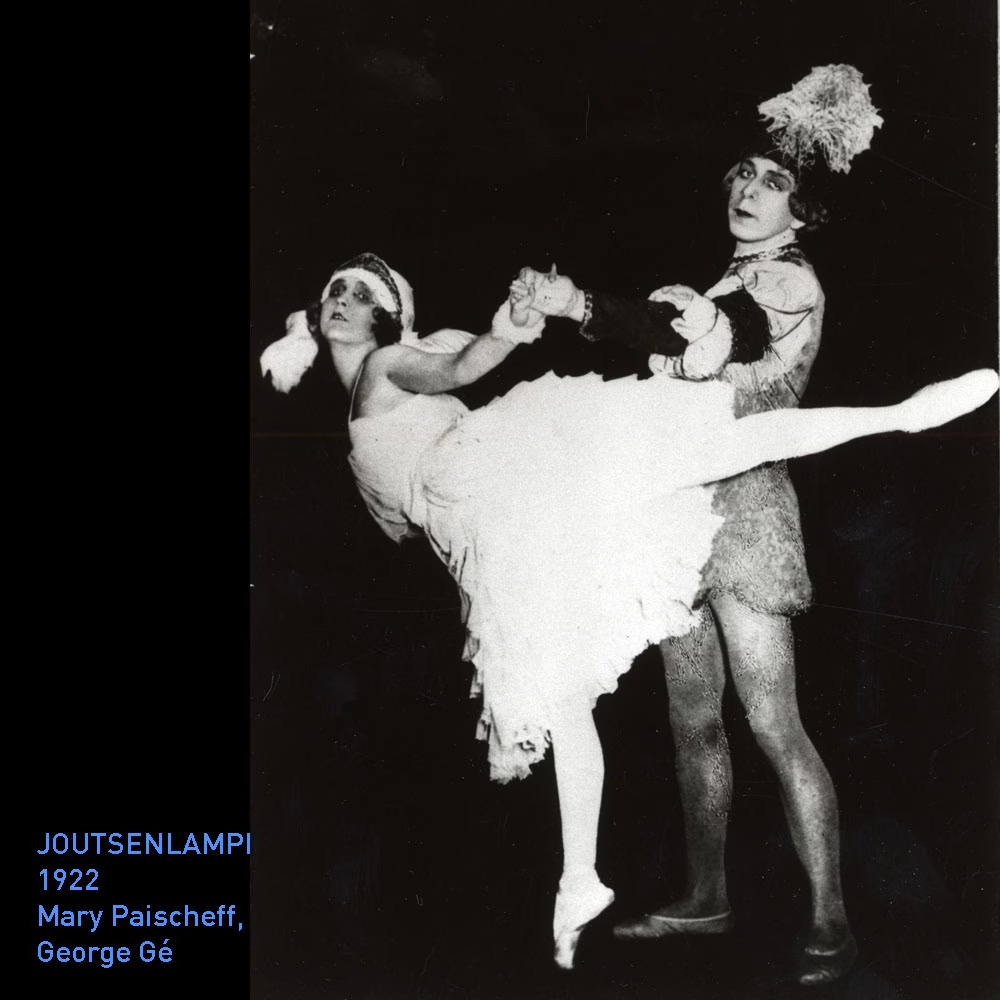

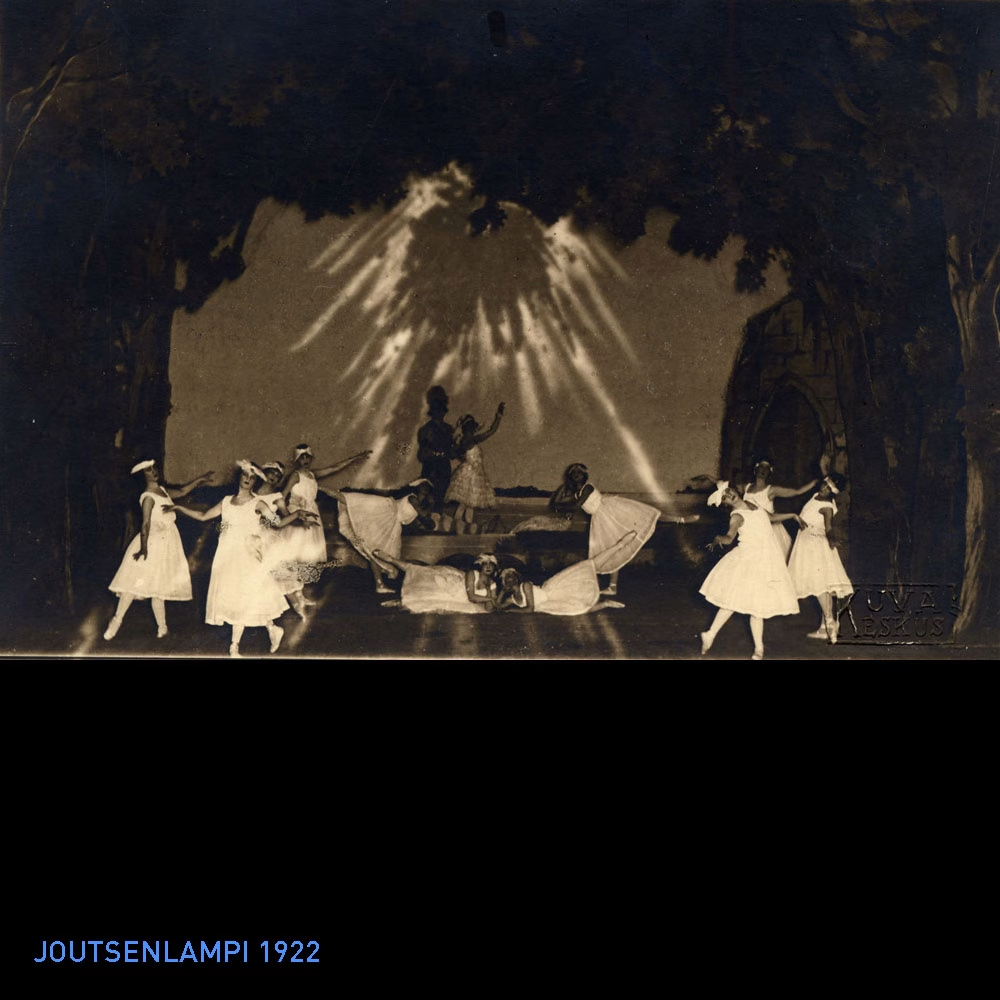

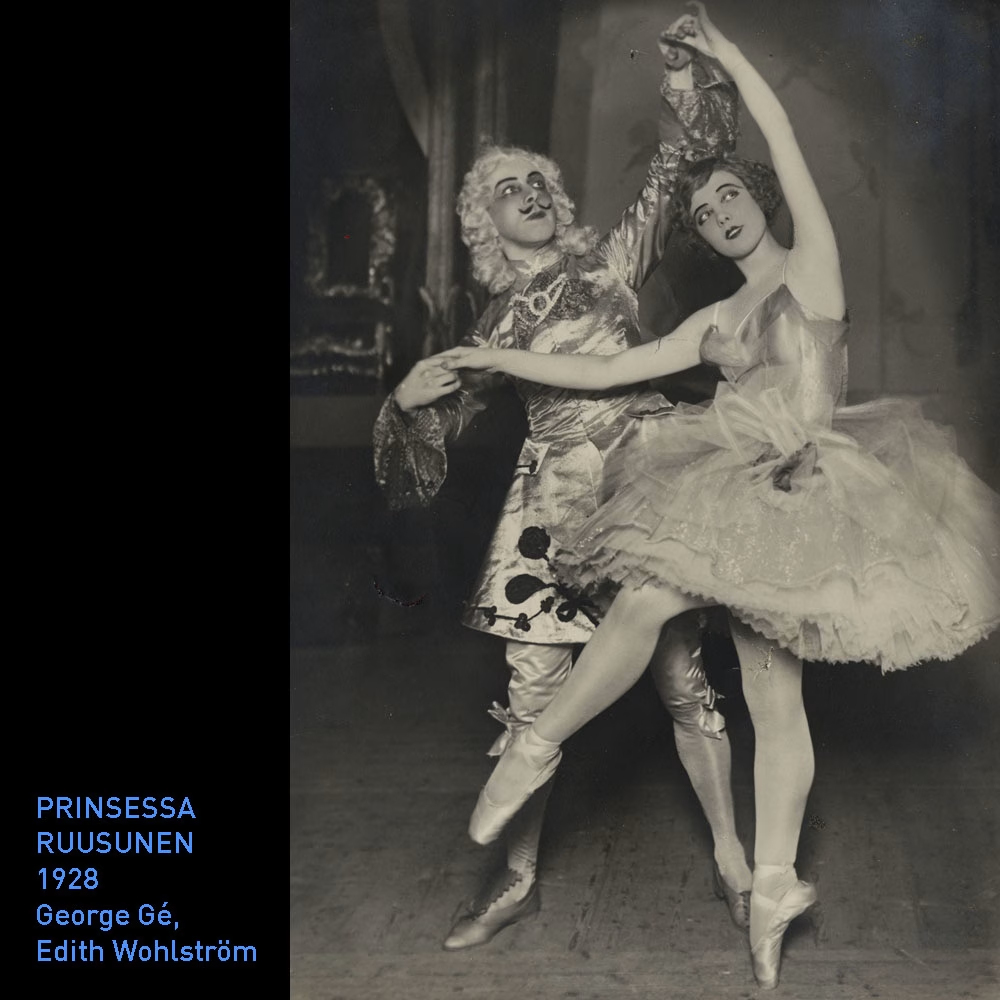

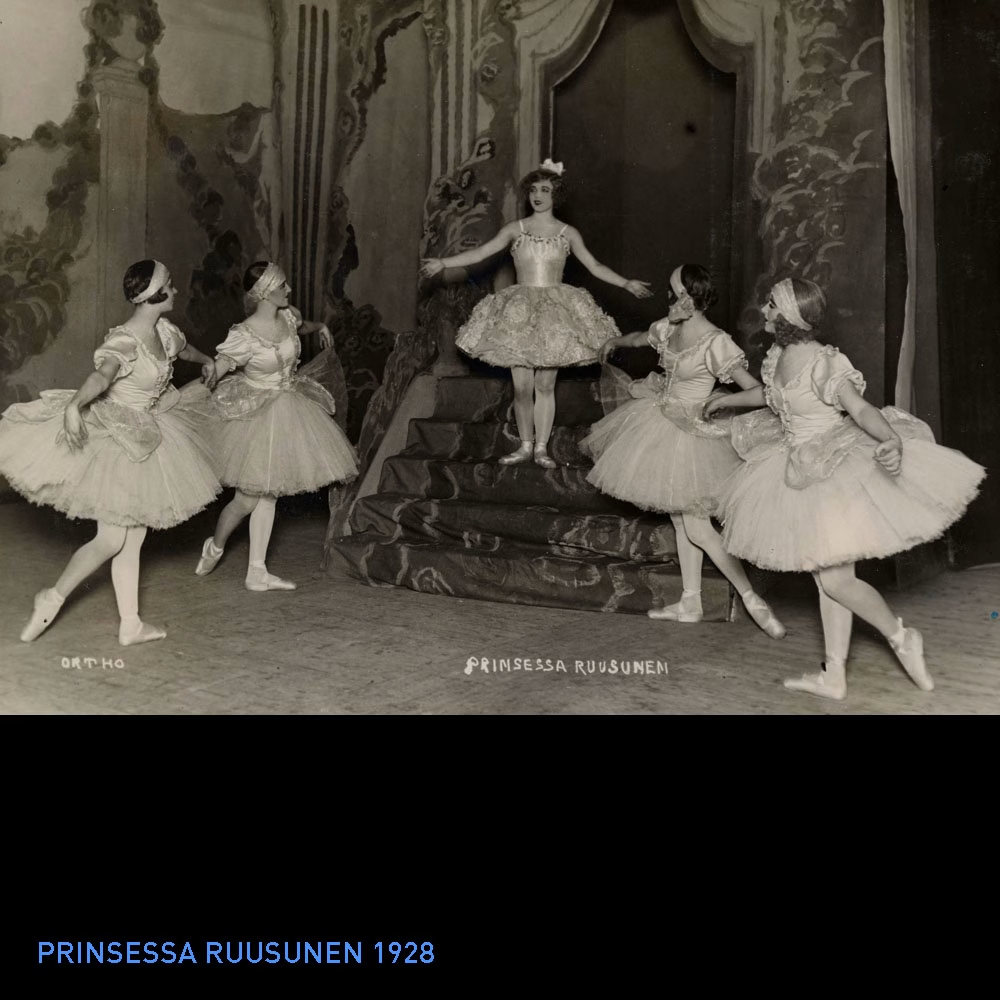

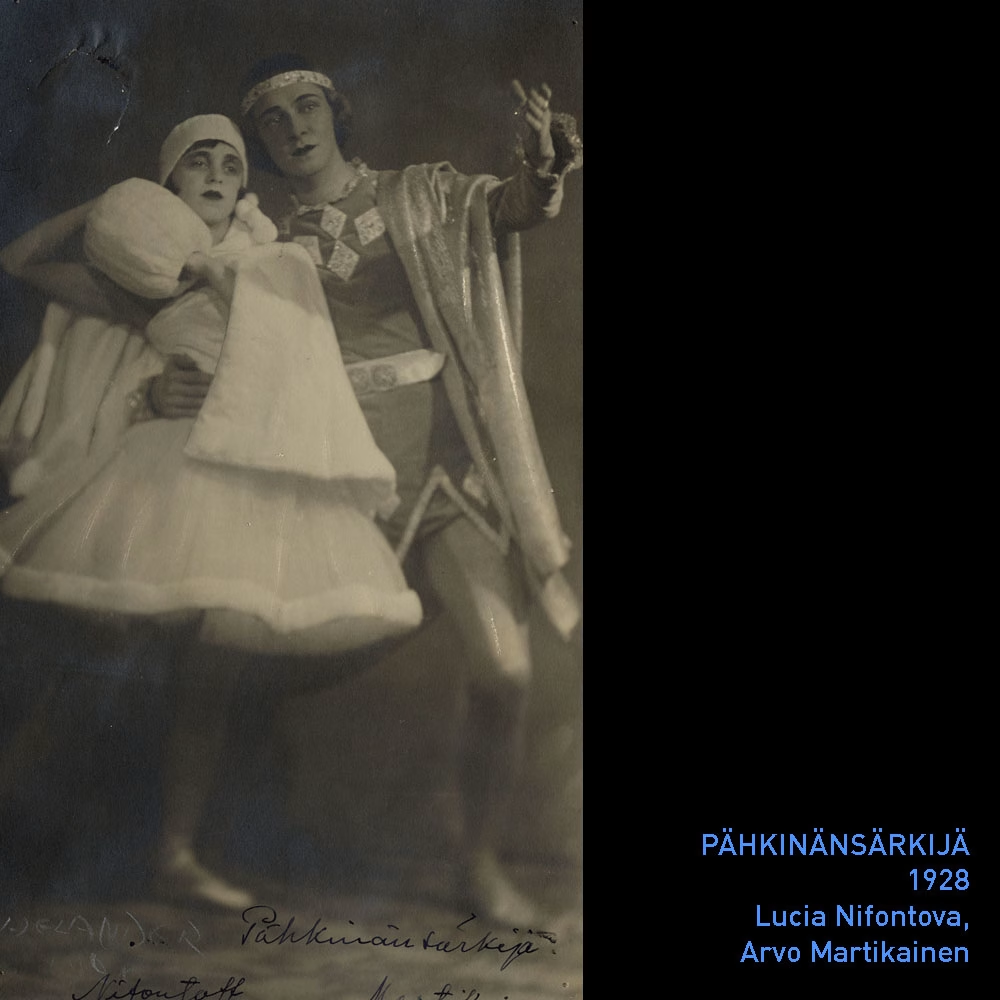

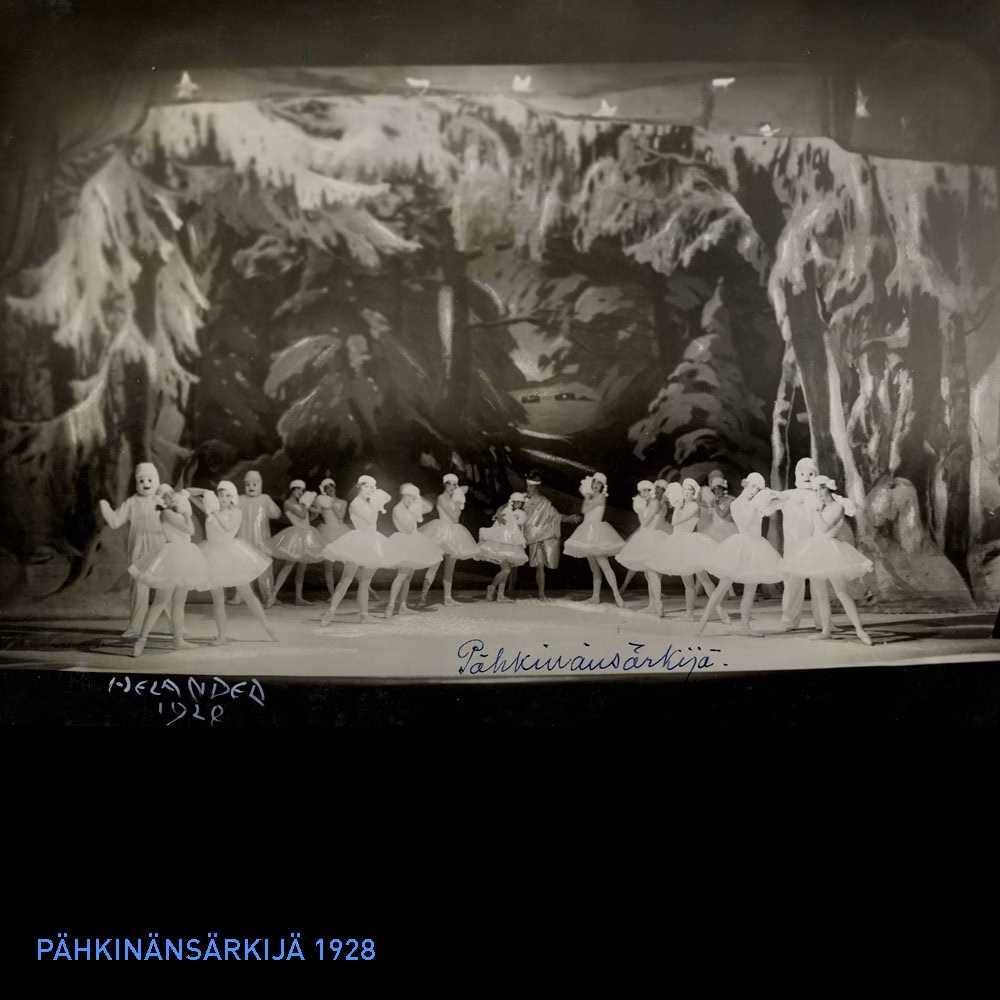

During the first decades, the majority of ballets at the Finnish Opera Ballet were choreographed by its ballet master George Gé. His choreographies were largely based on what he’d learned and noted down in St. Petersburg. Copyrights were not yet an issue in those days, so choreographers would borrow material more or less freely from works they’d seen elsewhere. Thanks to Gé, all Tchaikovsky’s ballets – Swan Lake, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, and The Sleeping Beauty – were already seen in Finland in the 1920s, though they didn’t premiere in most of Western Europe until the 1930s or later.

In the 1920s, Gé expanded the ballet company’s repertoire of Russian and French classical ballets with contemporary works, originally performed by Ballets Russes, and brand new choreographies to Finnish music. The first Finnish full-length ballet, The Blue Pearl, composed by Erkki Melartin and choreographed by Gé, had its world premiere at the Finnish Opera in 1931.

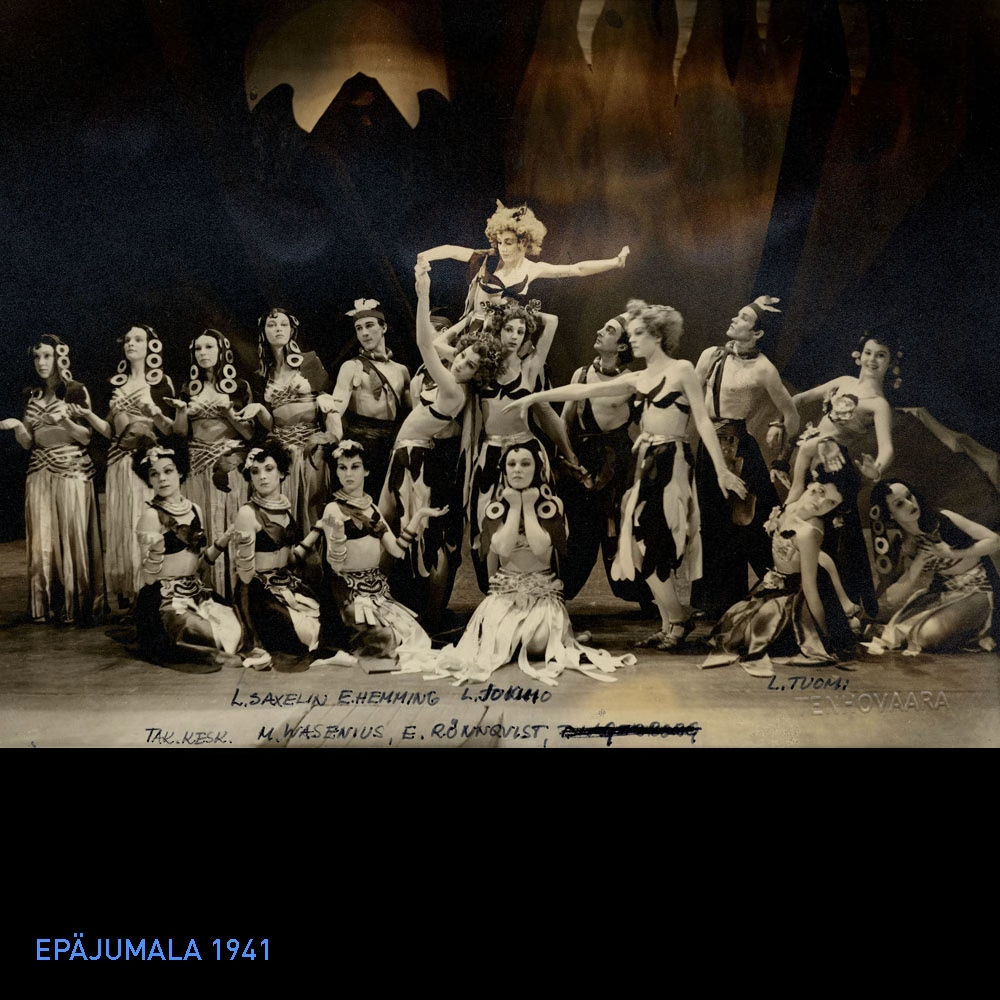

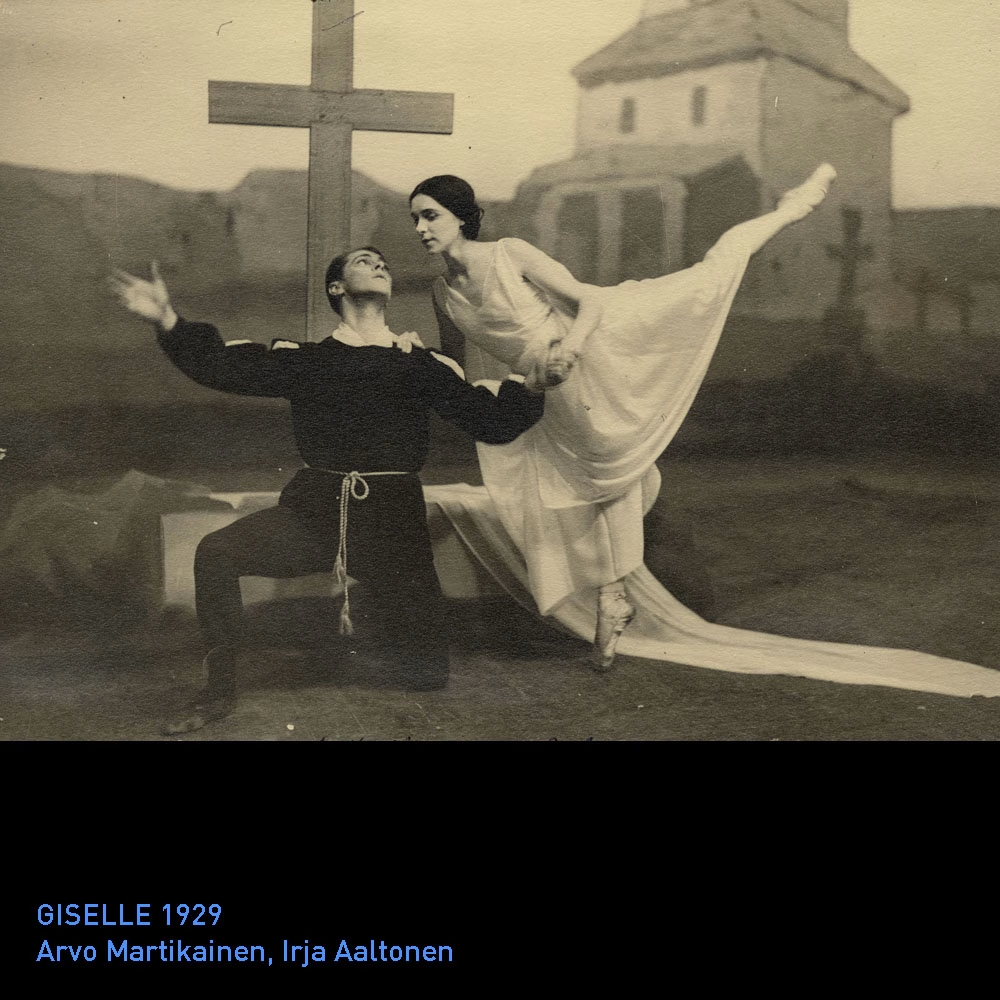

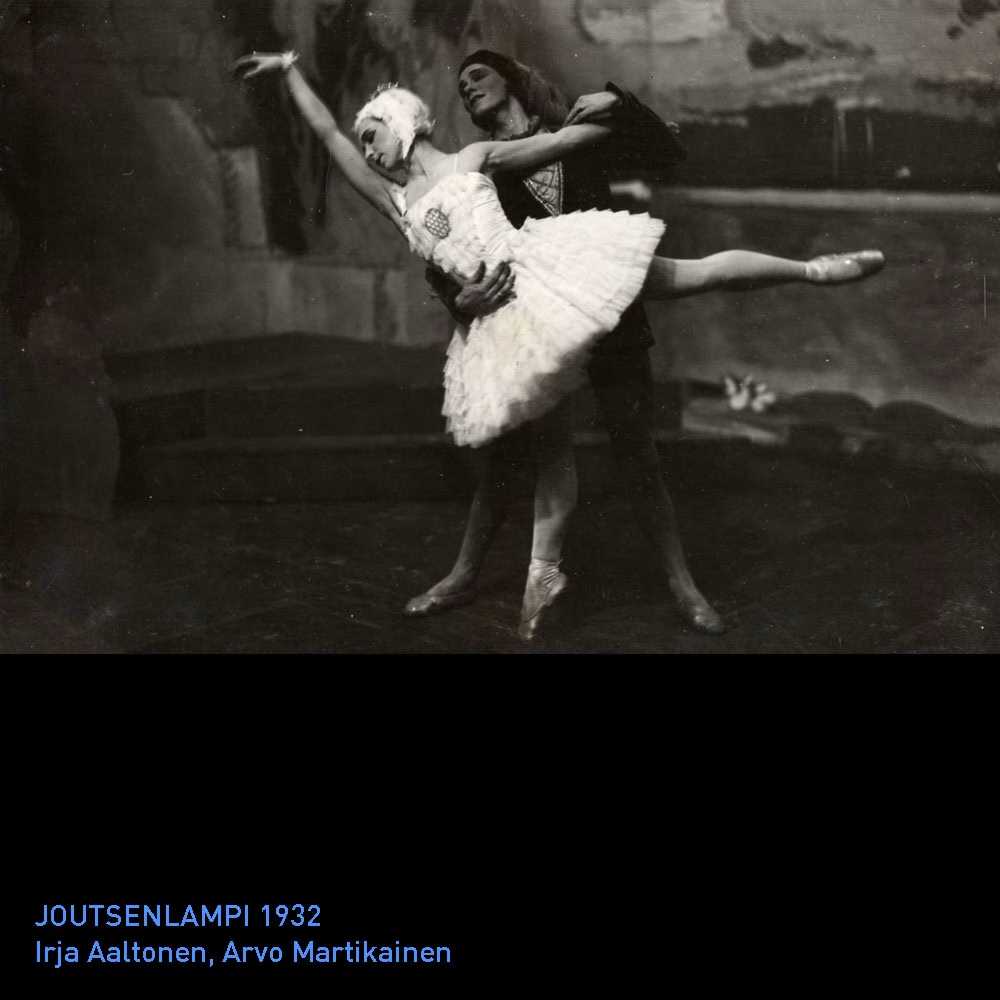

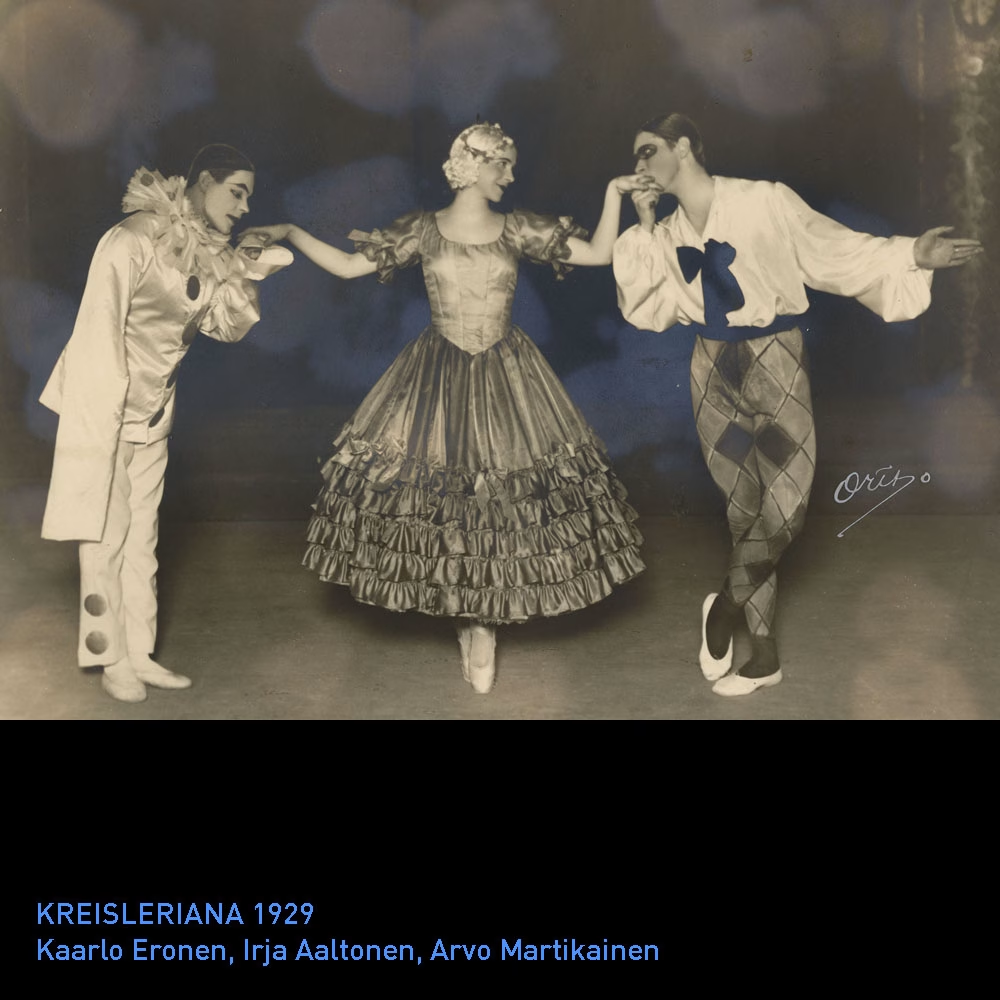

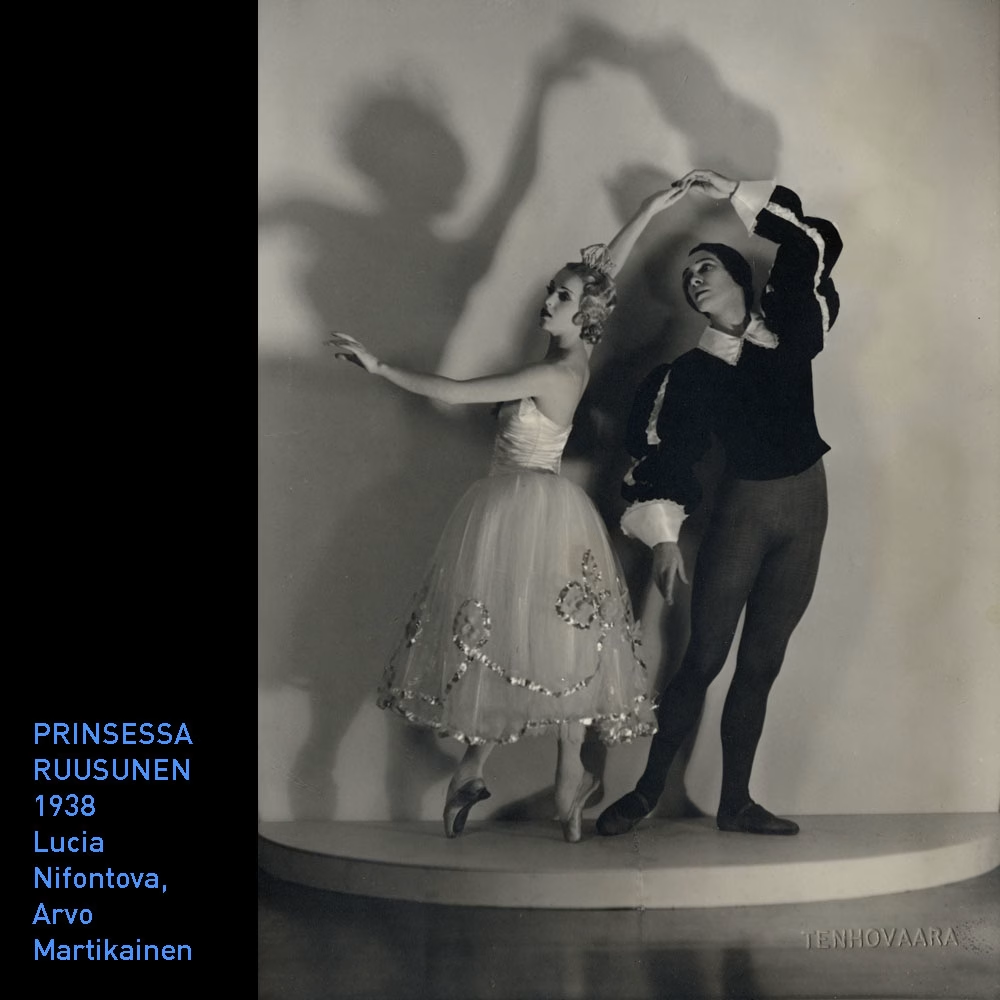

The Finnish Ballet showcased its first home-grown star at the end of the 1920s, when 16-year-old Lucia Nifontova had her career breakthrough in the lead role of Petrushka. Other leading dancers of the time included Irja Aaltonen and Arvo Martikainen.

The recession of the 1930s brought financial hardship to the Finnish Opera. Salaries, which were meagre to begin with, had to be cut. Radical plans to save the opera company included stopping the production of operettas, which were popular but expensive. That would have meant less work for dancers, and at one stage it looked like the entire ballet company would be closed down. The idea, however, sparked considerable outrage, and operettas and the Finnish Ballet were allowed to stay. By then, however, ballet master Gé and the company’s lead soloists, Nifontova and Martikainen, had already decided to move on to the Ballets de Monte Carlo.

Saxelin takes over as ballet master

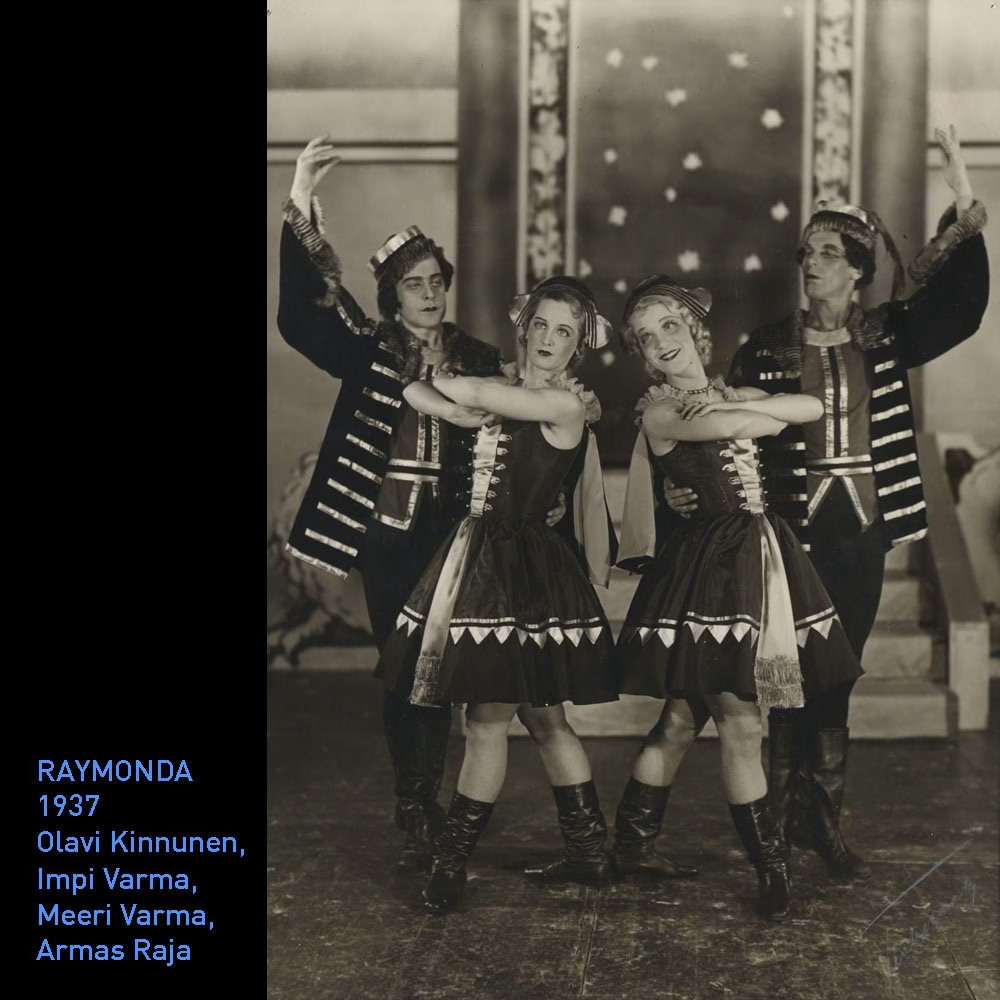

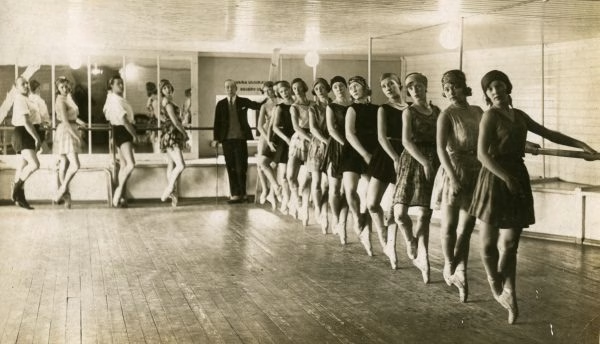

After the departure of George Gé, the Finnish Opera needed a new ballet master to continue his work. The critics of Gé had been pushing for his replacement with Alexander Saxelin since the 1920s. Saxelin, who had completed his ballet education in St. Petersburg, had danced in St. Petersburg and the Finnish Opera Ballet, as well as run his own ballet school for years. He was promptly appointed as Gé’s successor, and his pedagogical expertise proved one of his key strengths. Saxelin recruited new dancers to replace the stars who’d left for Monte Carlo, while one of the ballet company’s own talents, Irja Koskinen, was appointed as its prima ballerina.

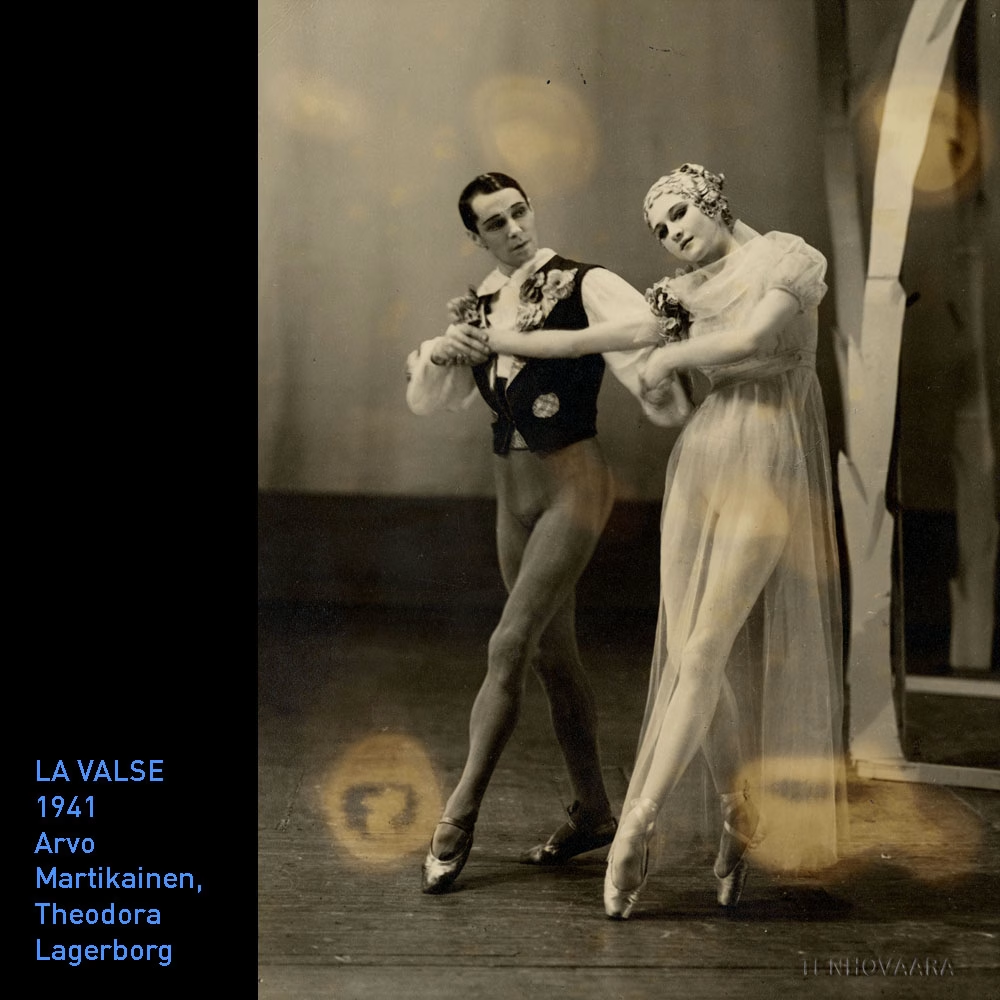

Saxelin hadn’t been in charge for long when Gé, Nifontova and Martikainen began planning their return to Helsinki. The two dancers had been building a successful career abroad, but they found touring Europe taxing and rejoined the Finnish Opera Ballet in 1938. Gé was harking back to his ballet master role, but he had to wait for his turn.

After the Winter War, in autumn 1940, Saxelin embarked on a tour of the Nordic countries with Irja Koskinen and Robert Niko. A familiar face from the Royal Swedish Ballet, George Gé, took over his responsibilities. During the interim peace, while Central Europe was ravaged by war, Gé continued to work as a ballet master in both Stockholm and Helsinki. Saxelin returned to his role during the Continuation War, staging his first premiere while on leave from his medic duties on the front.

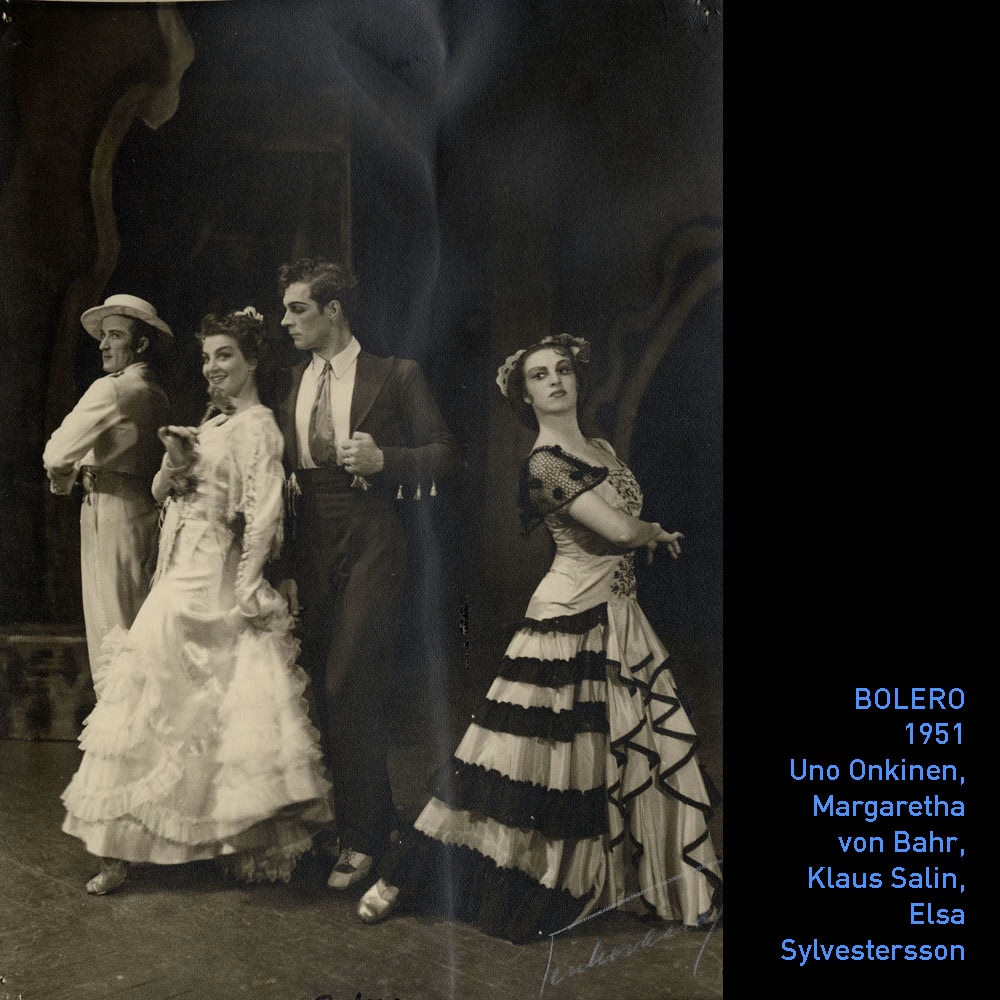

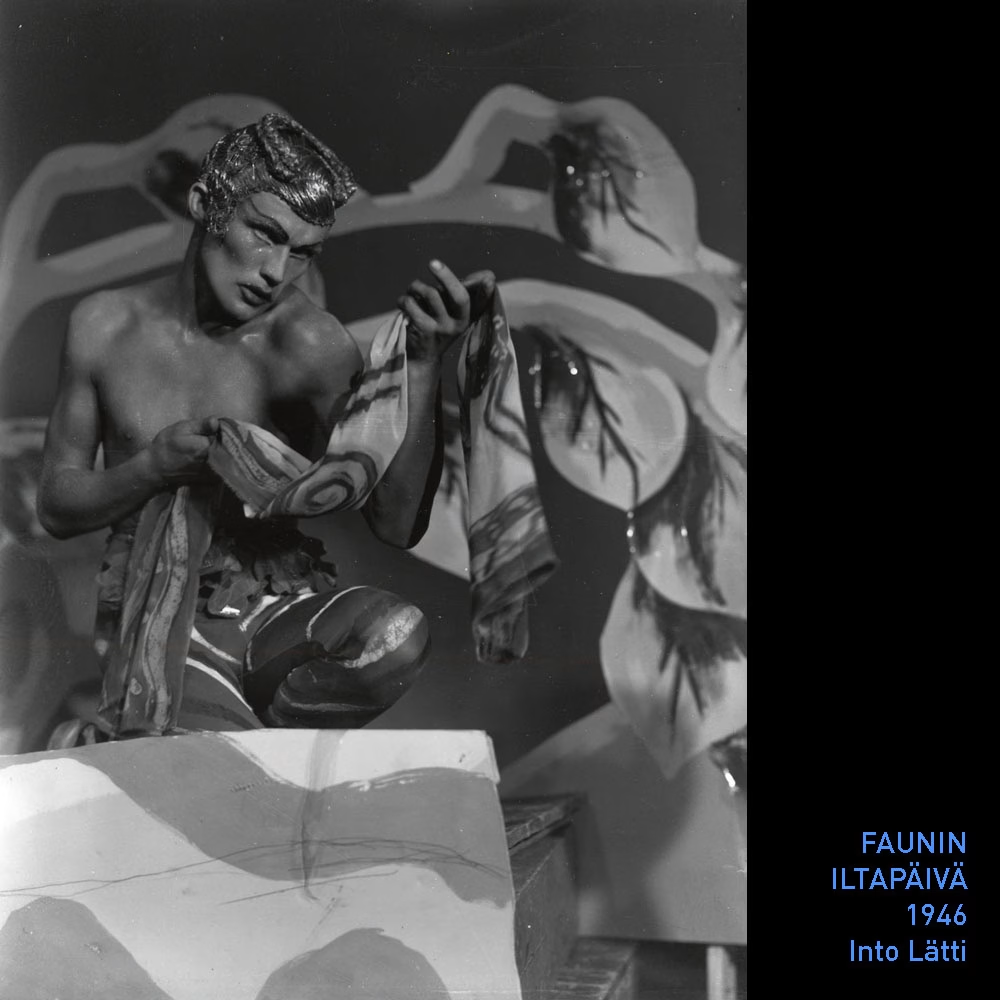

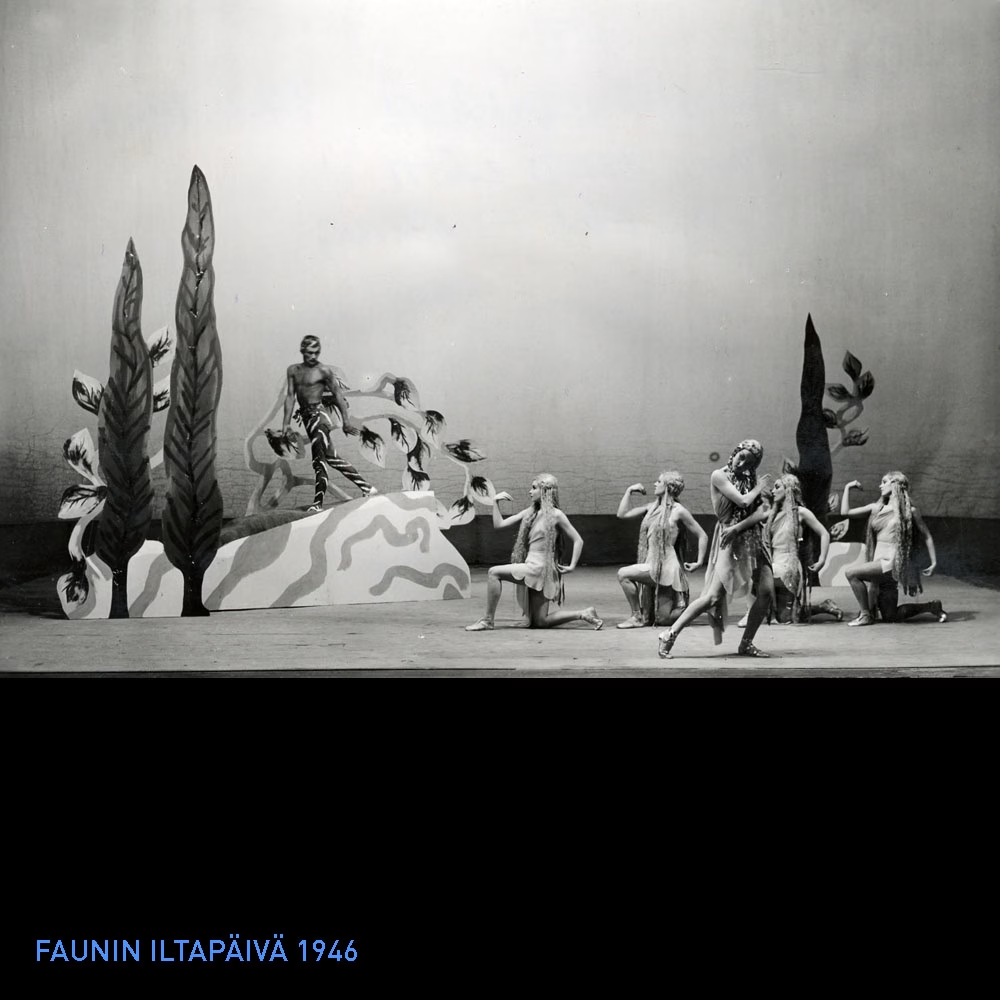

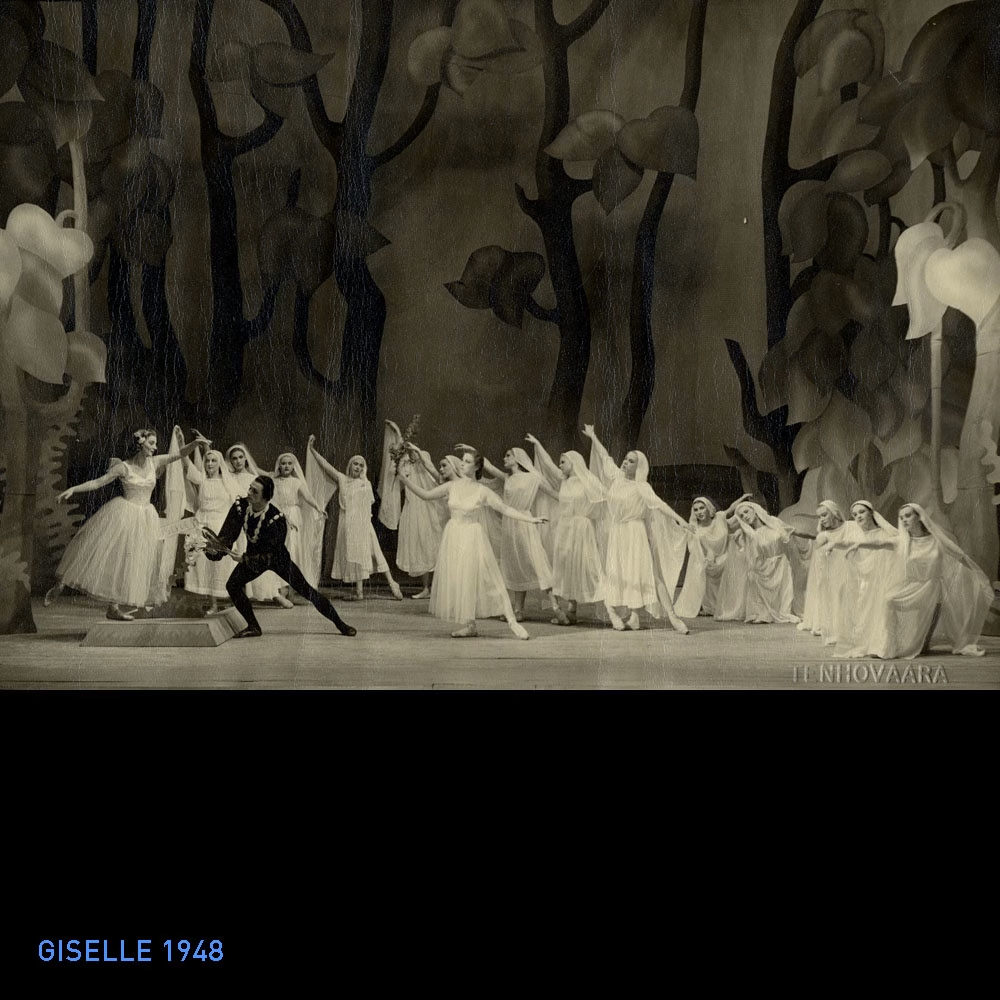

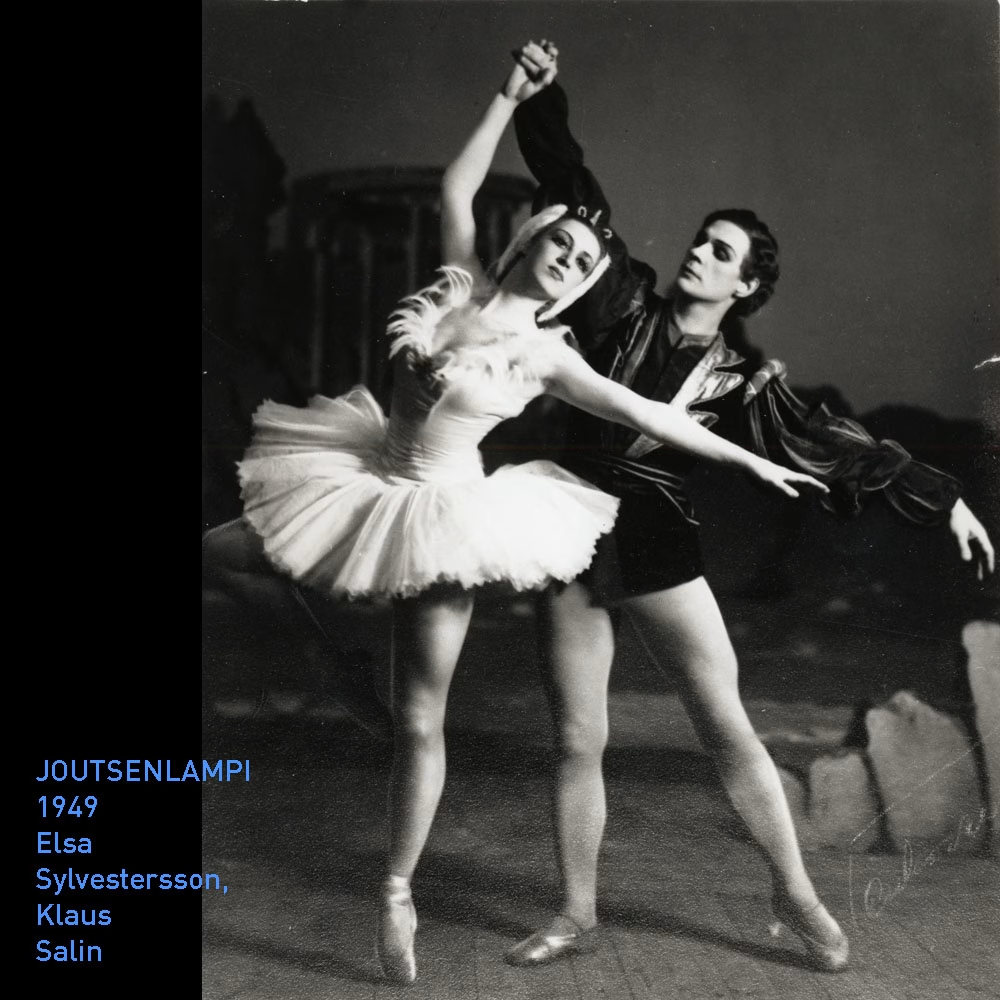

Guest choreographers were a regular feature during Saxelin’s tenure, and eventually Saxelin completely stepped aside as a choreographer. The first foreign choreographer who collaborated with the Finnish Opera Ballet was Julian Algo, the German-born ballet master of the Royal Swedish Ballet, in the late 1940s. Maggie Gripenberg, Irja Koskinen, Elsa Sylvestersson and Birgit Cullberg also made their choreographer debuts at the Finnish Opera Ballet.

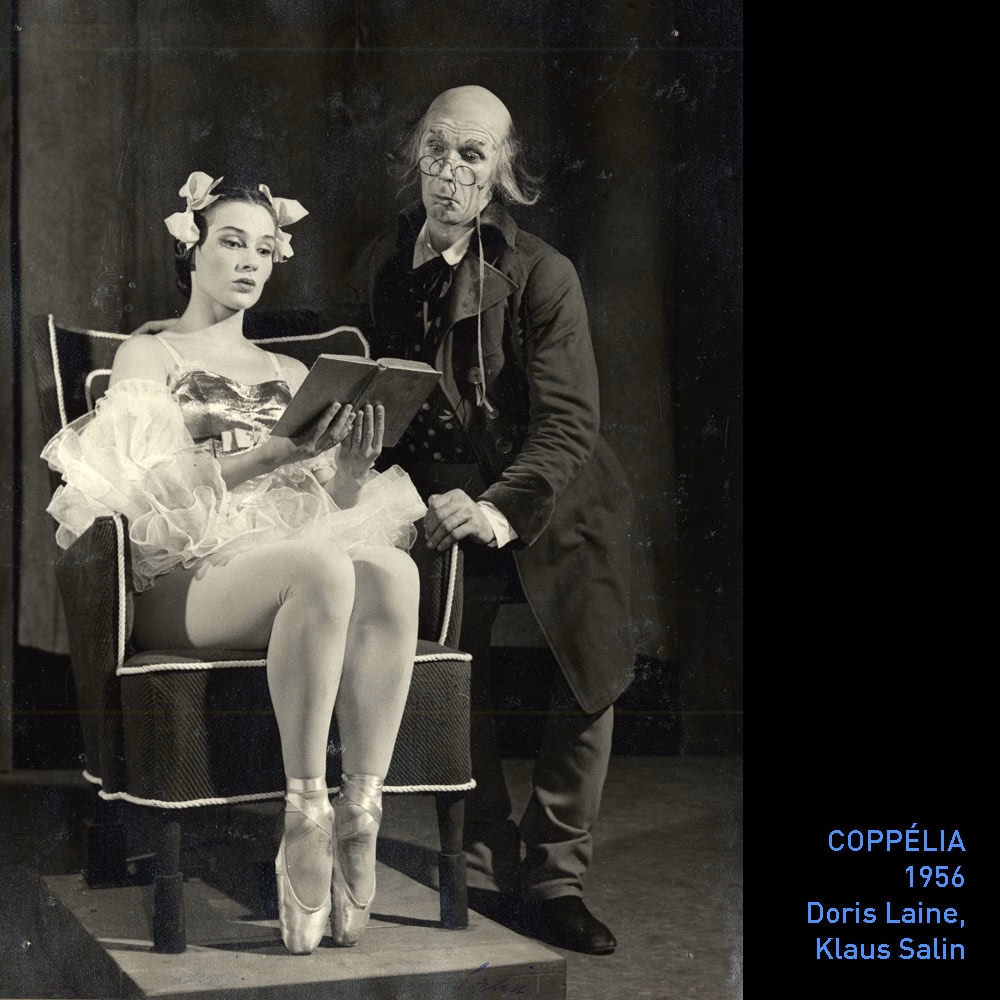

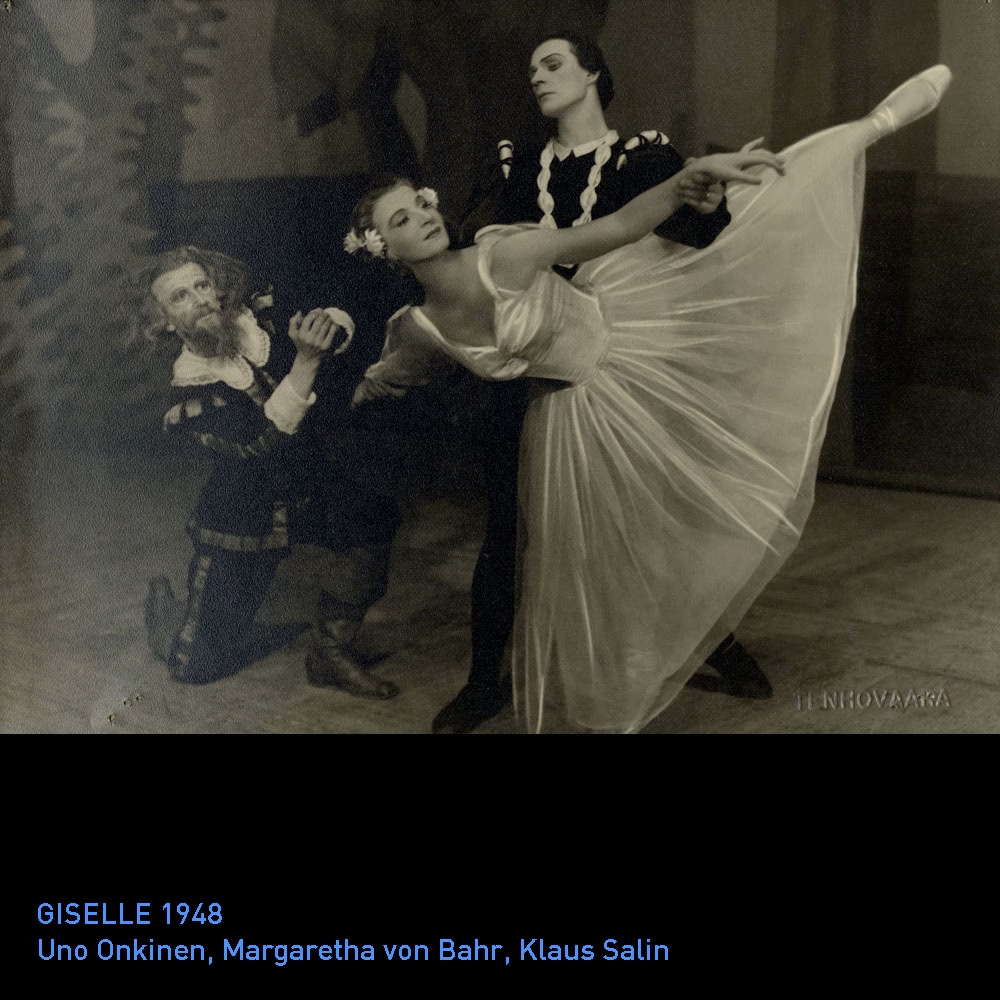

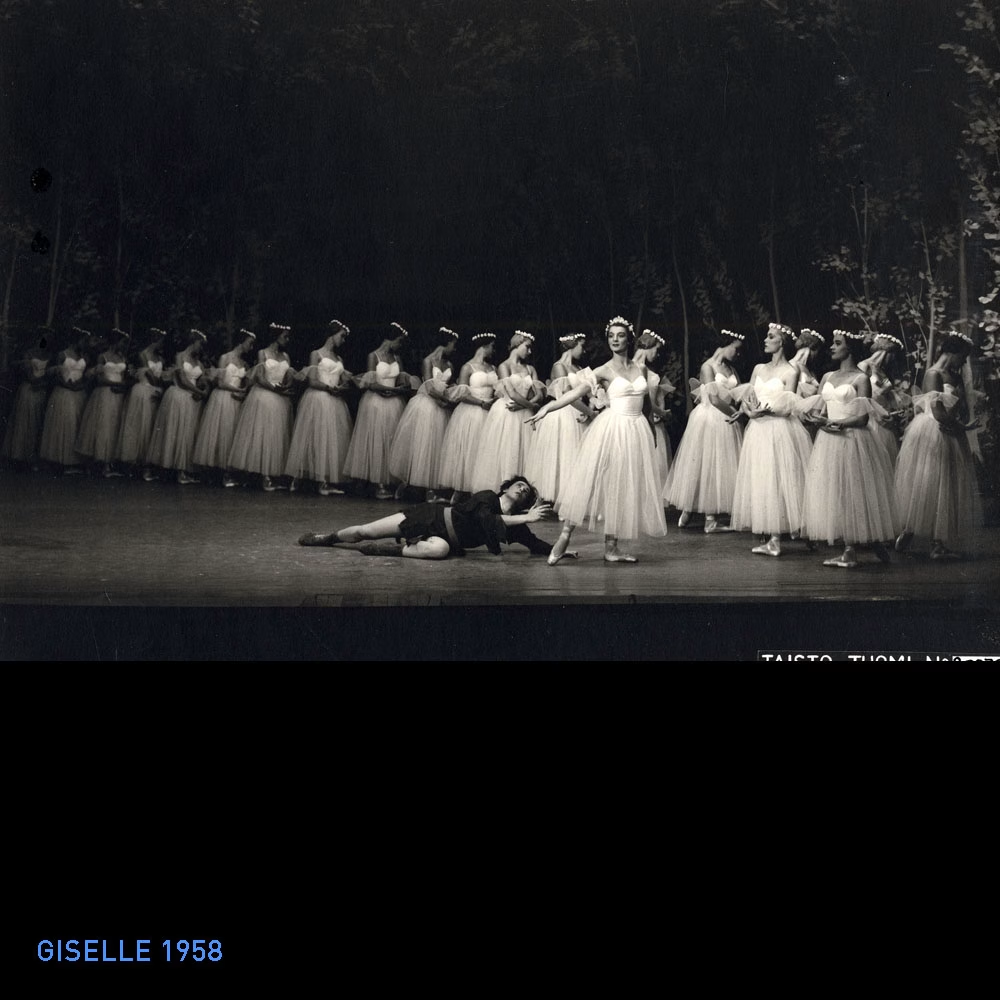

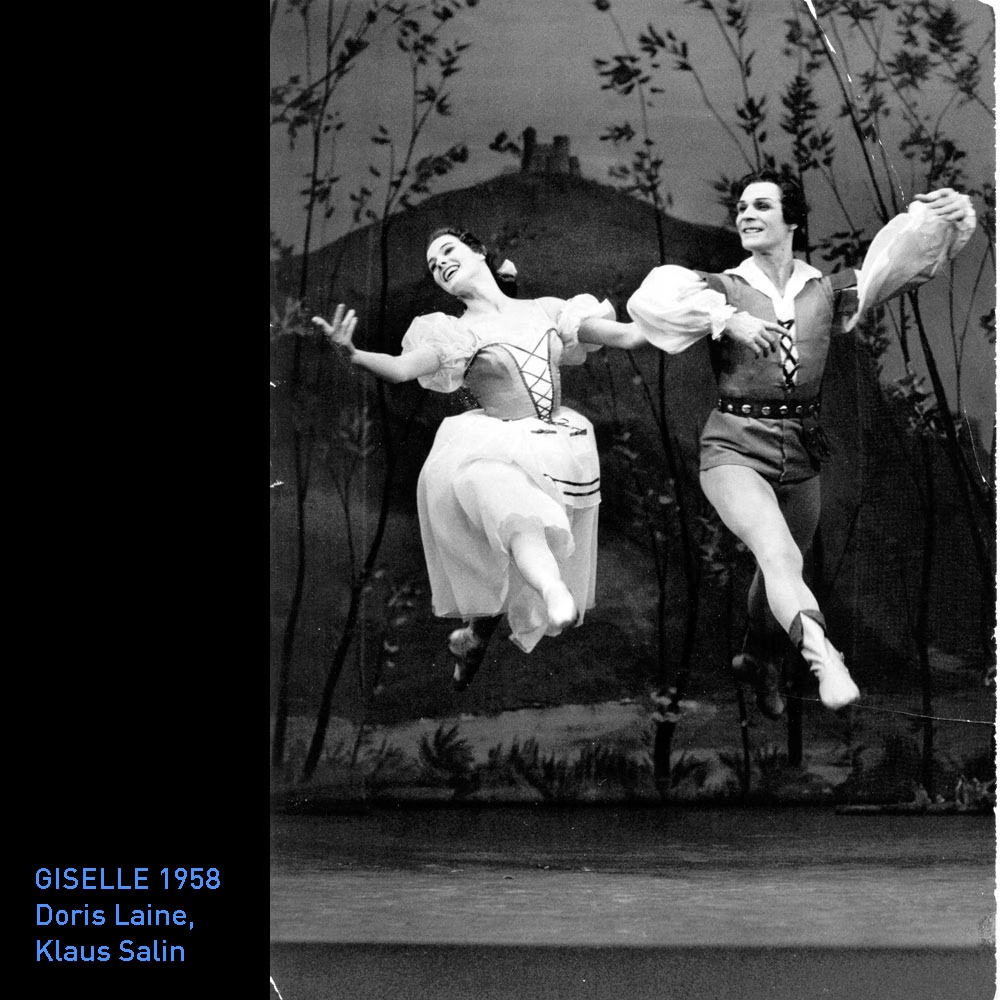

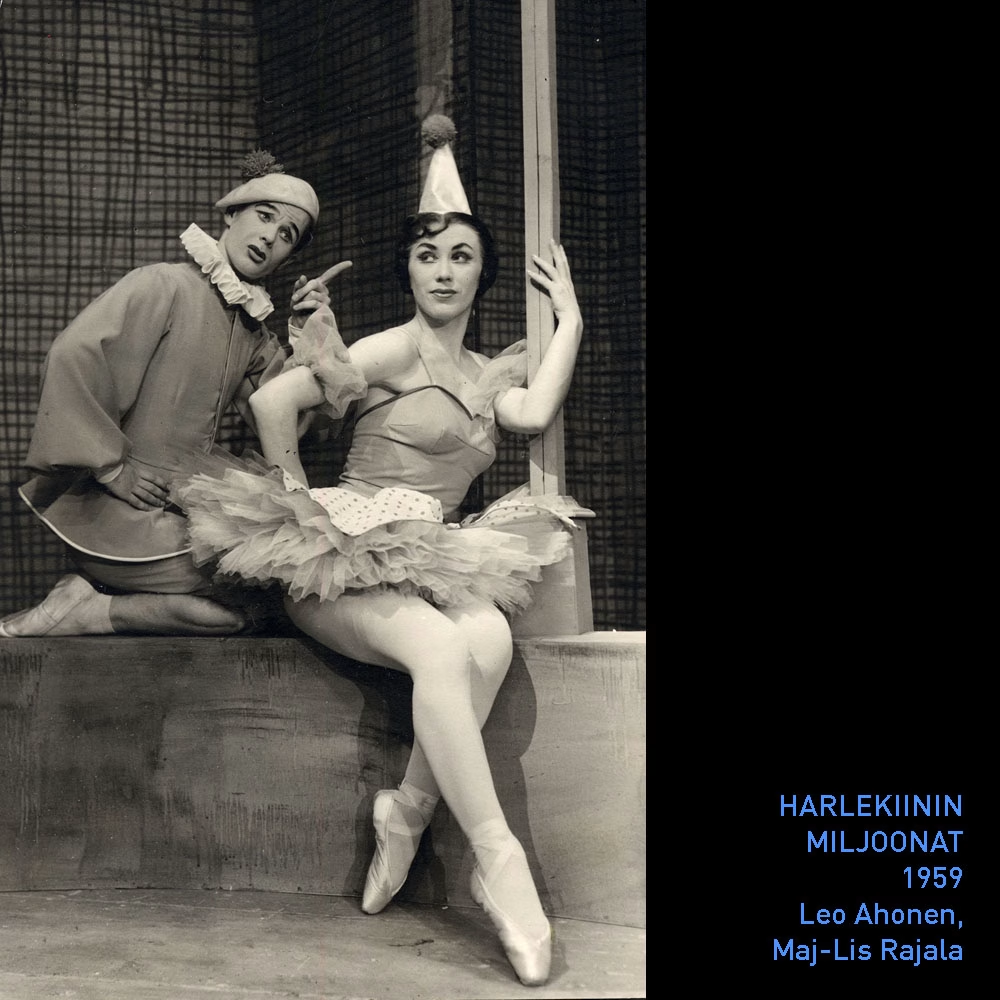

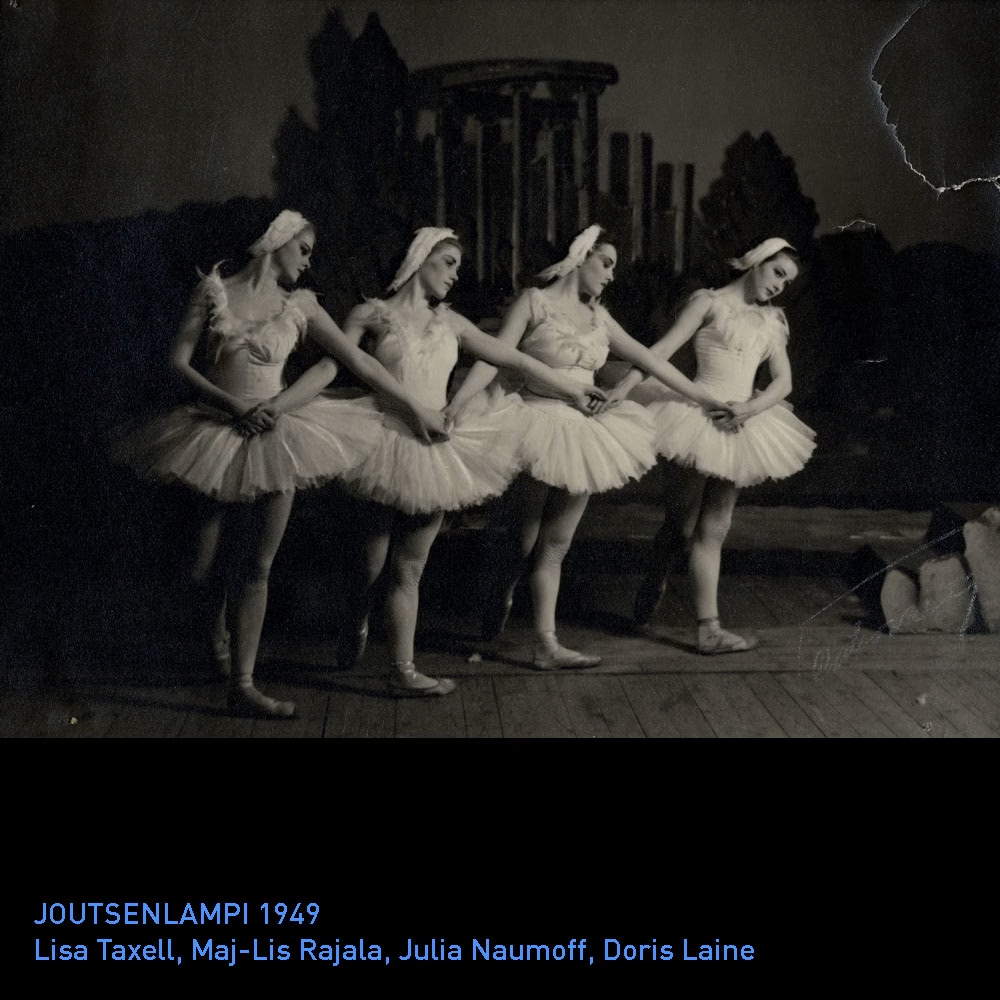

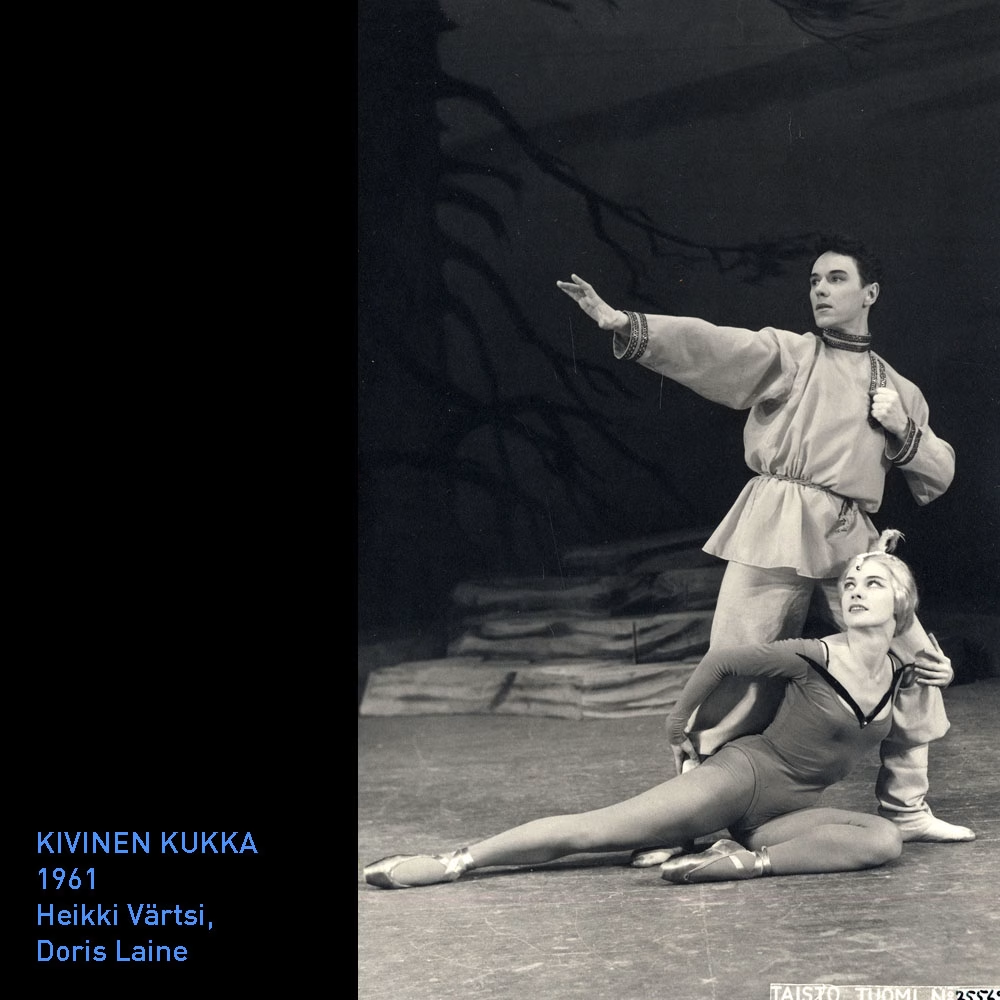

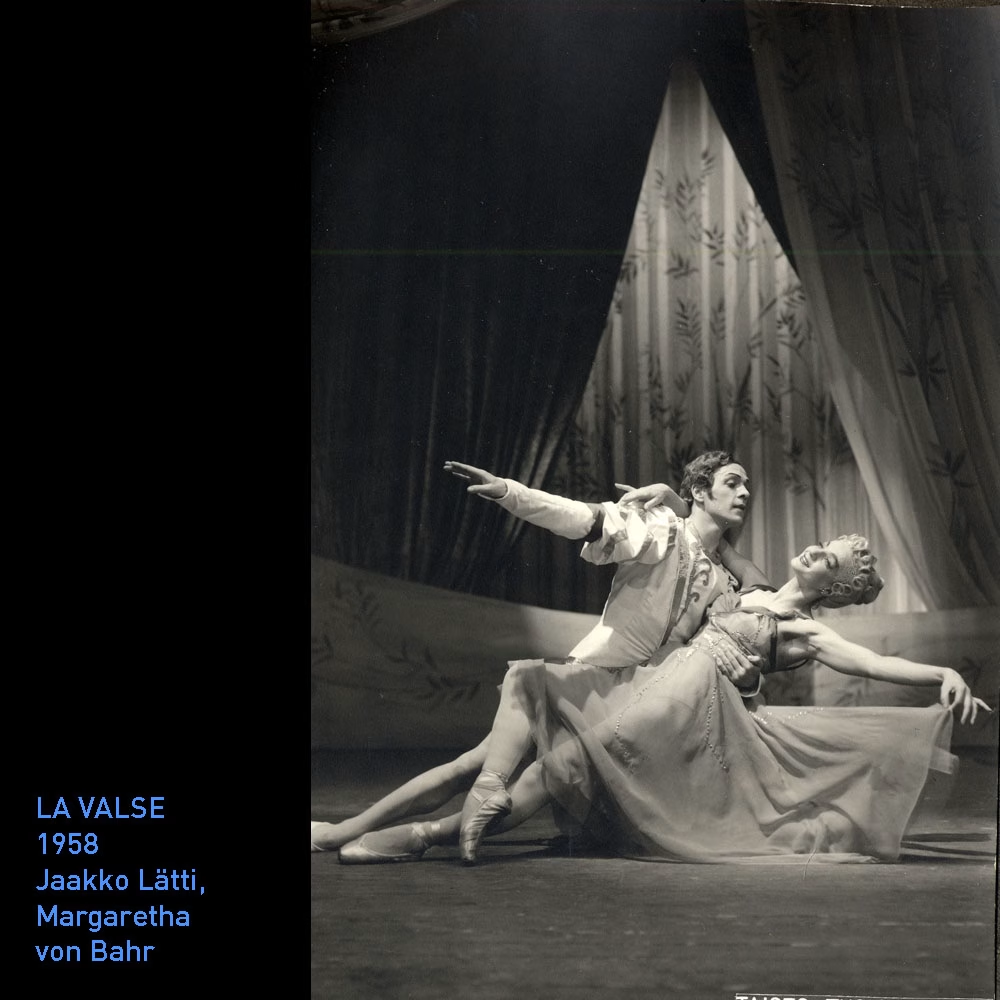

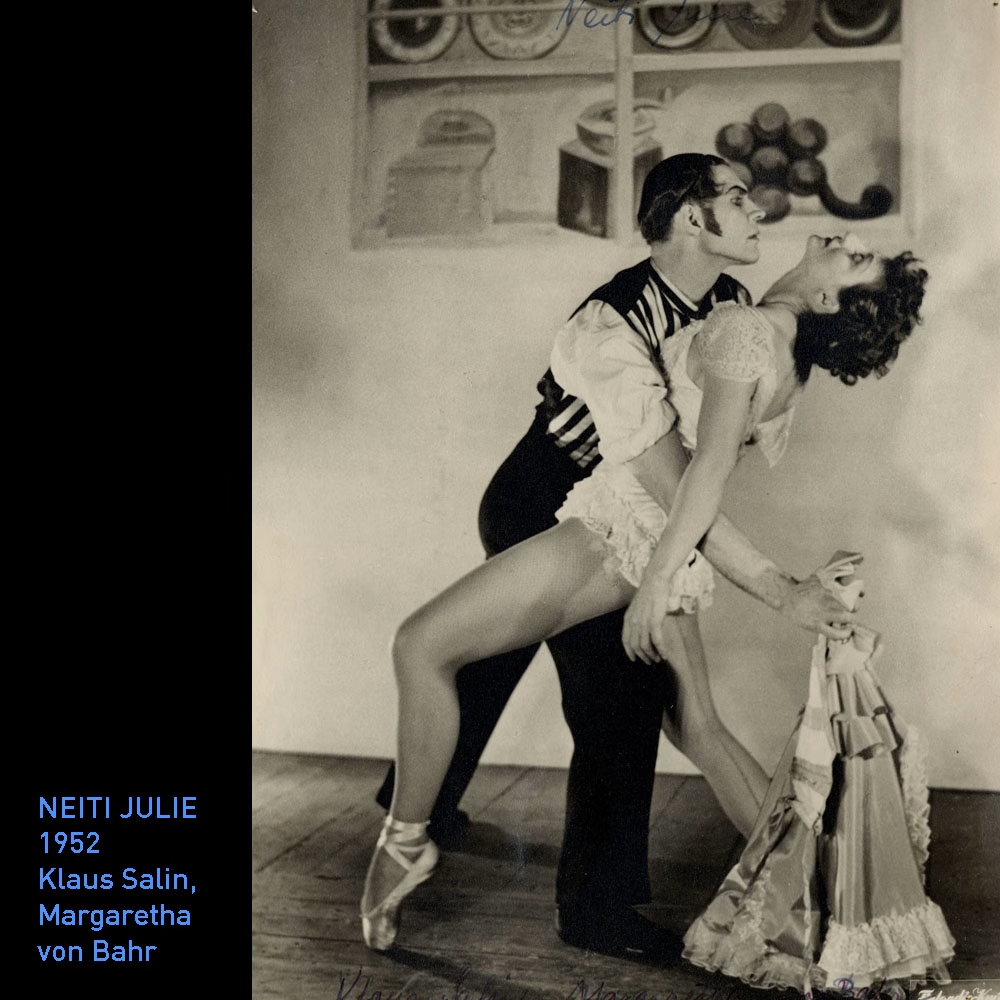

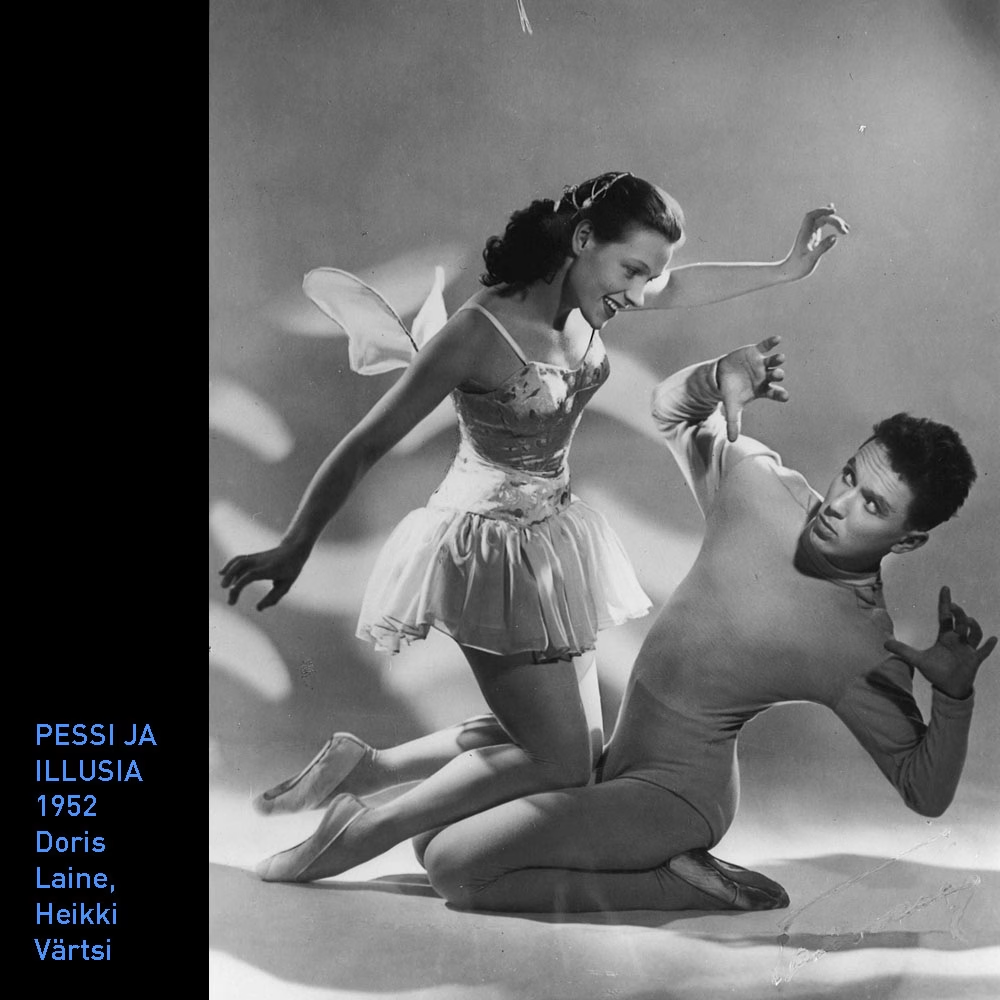

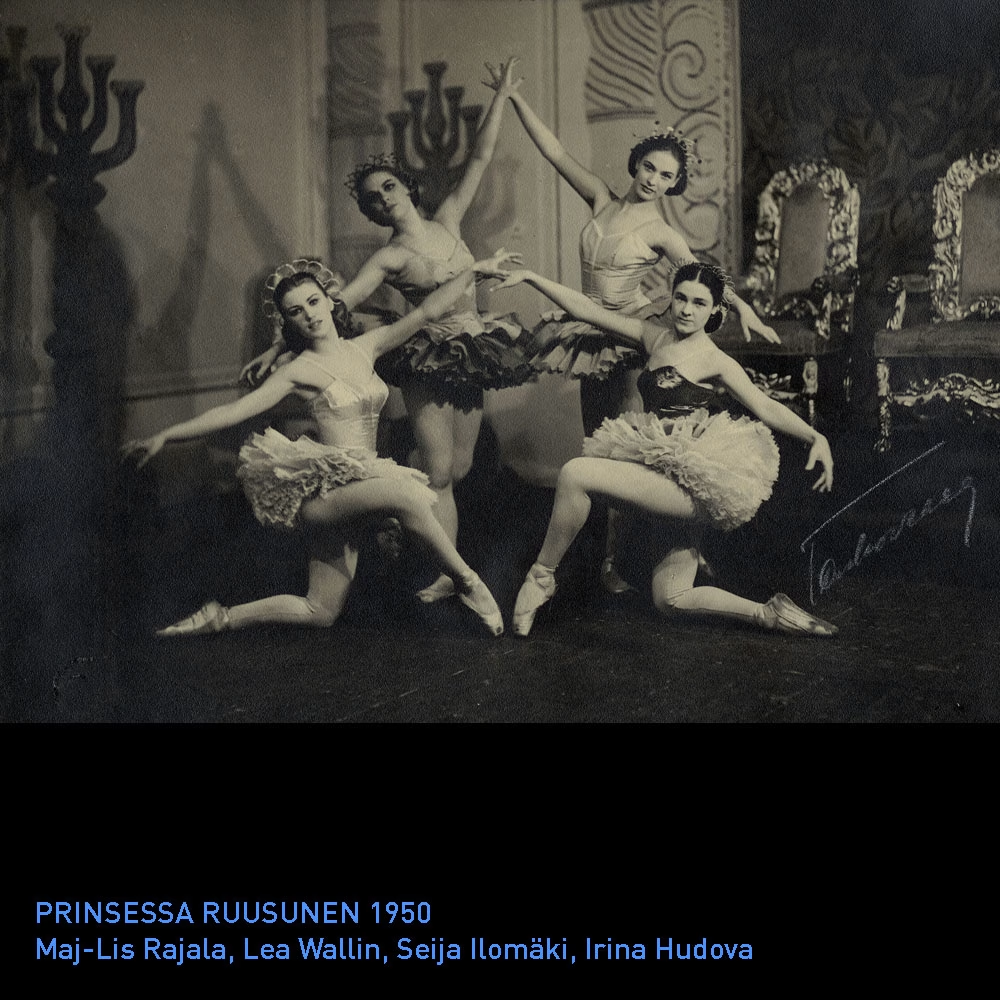

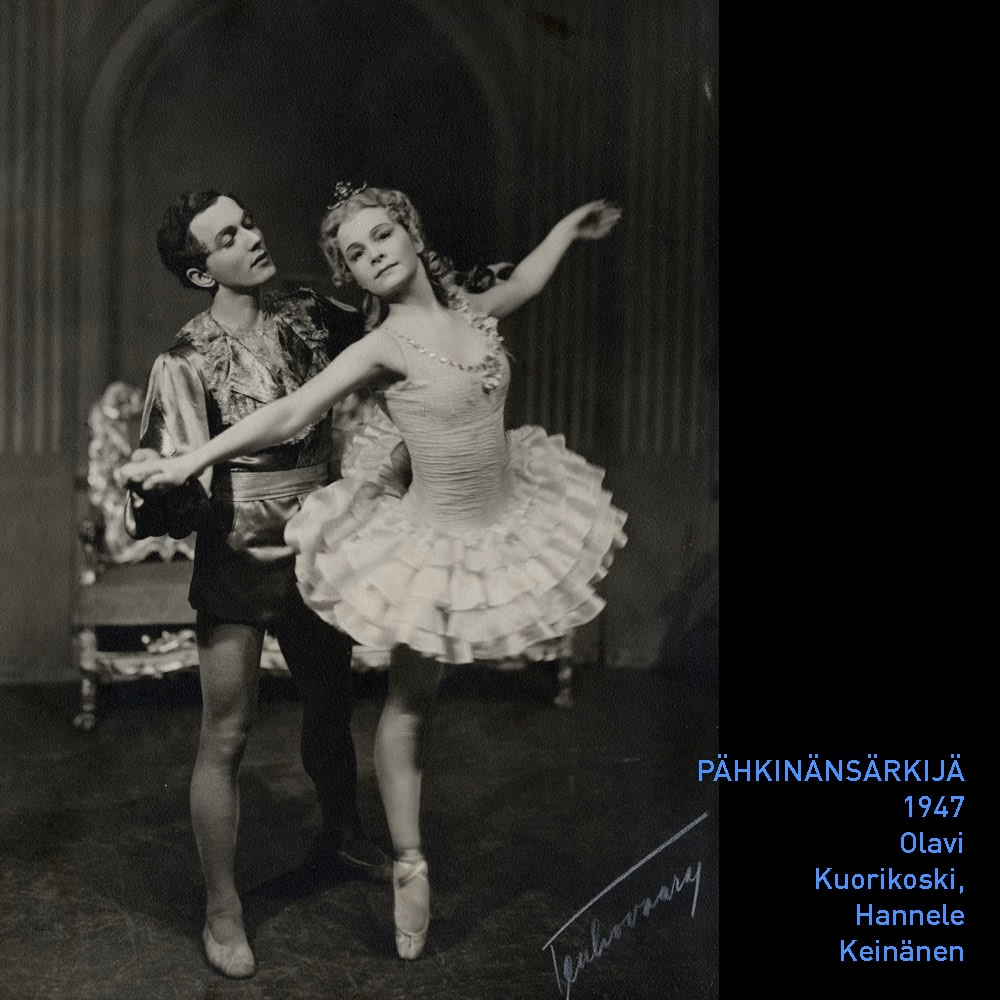

Saxelin trusted the young, home-grown talents of the Finnish Opera Ballet, giving them central roles in many productions. Ballerinas who made their debuts in wartime included Margaretha von Bahr and Elsa Sylvestersson. Soon after the war, Finnish dancers finally got to showcase their skills in other Nordic countries. Feeling under-appreciated at home, they accepted invitations to join ballet productions and companies abroad. Saxelin had no choice but to train teenage dancers as his new soloists. Hannele Keinänen was given the role of Odette/Odile at the age of just 19, while the few years younger Doris Laine and Maj-Lis Rajala danced as little swans. Prominent post-war male dancers included Uno Onkinen and Klaus Salin.

Gé makes a comeback

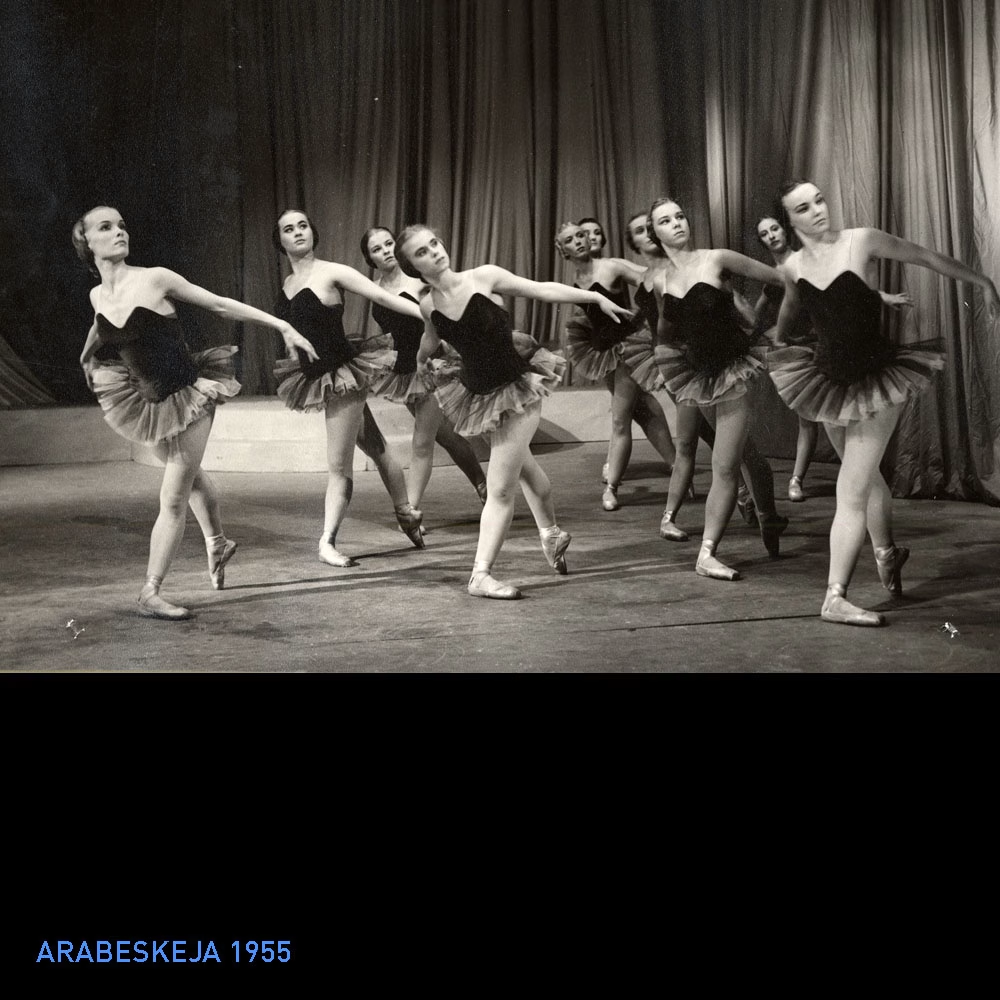

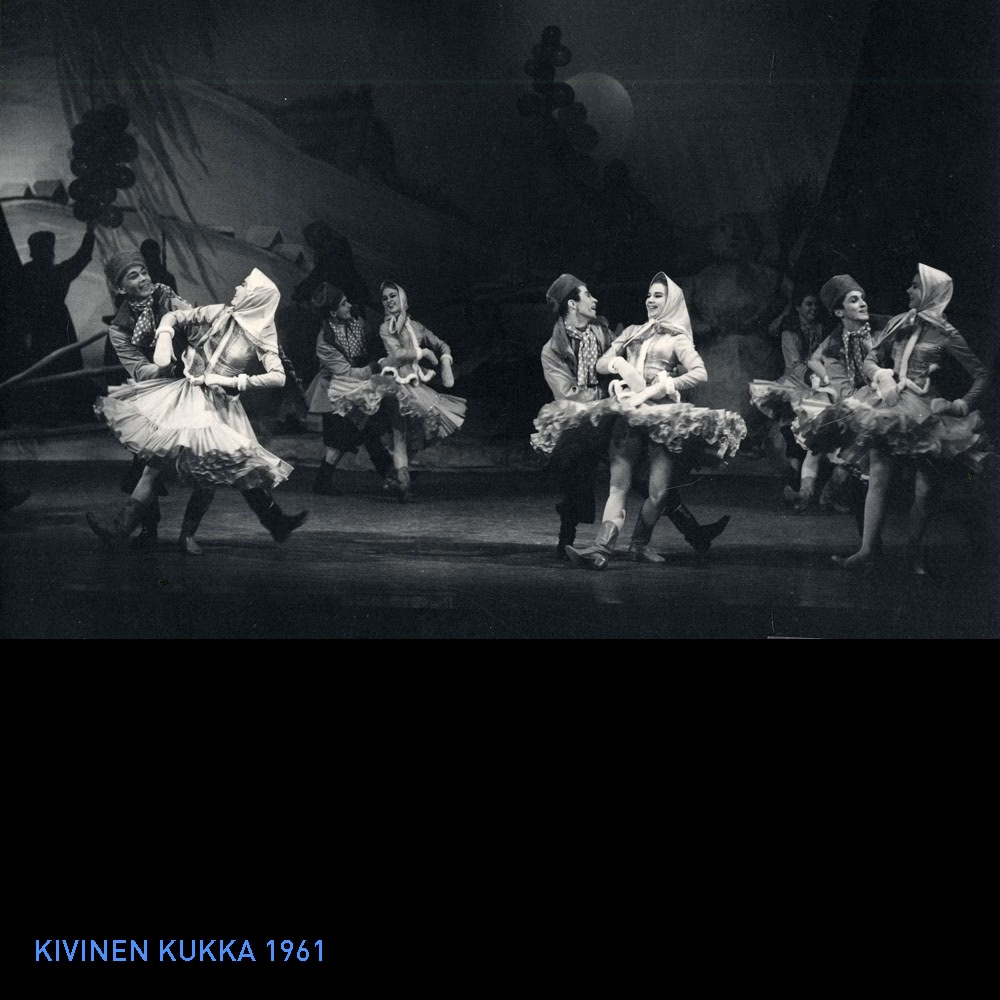

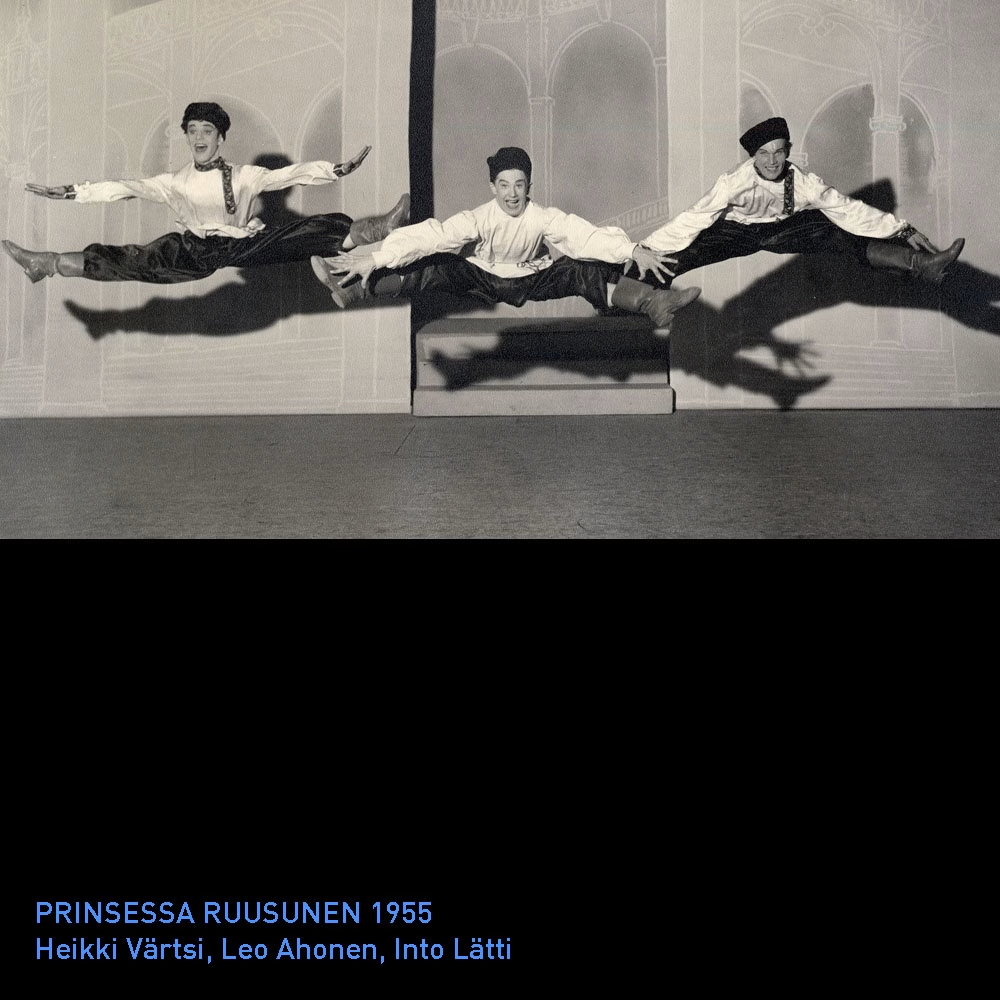

When Alexander Saxelin retired in 1954, finding a new ballet master turned out to be a challenge. Finally, the 62-year-old founder of the ballet company, George Gé, came to the rescue, resuming charge in 1955. The arrangement was meant to be temporary, but Gé stayed for another seven years. He initially focused on his own choreographies, many of which had premiered in France, but his second season was more varied and international, featuring several guest choreographers.

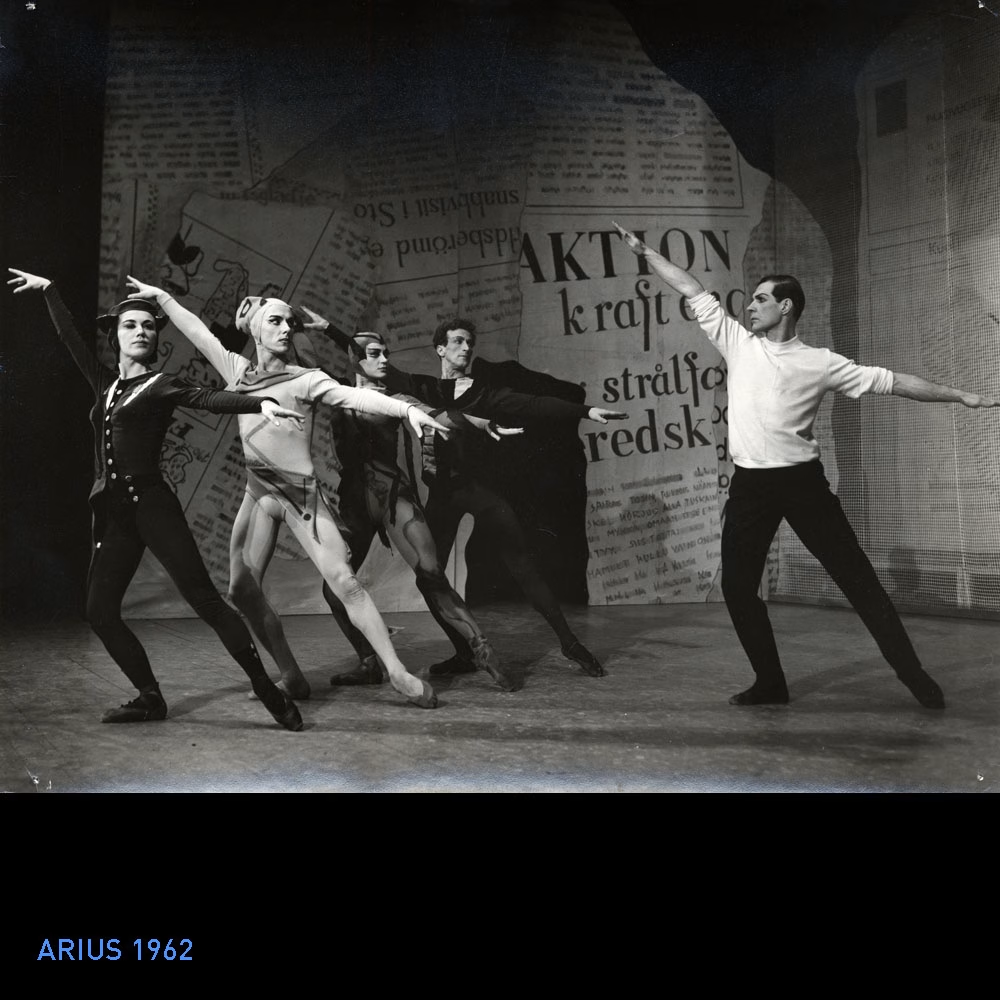

In 1958, Elsa Sylvestersson held a double role as a prima ballerina and an assistant ballet master, and Gé delegated an increasing amount of choreography duties to her. Sylvestersson’s work was heavily influenced by the new neoclassical ballet style created by George Balanchine, who had risen to global fame in New York. Retirement was suggested to Gé in 1962, and he died shortly after ending his career at the age of 69. Young dancers who rose to soloist fame during Gé’s latter tenure included Seija Silfverberg, Leo Ahonen, Martti Valtonen, Seija Simonen, Fred Negendanck, Virpi Laristo, and Saga Eriksson.

Choreography copyrights became a talking point in the 1950s. Before the wars, ballet masters would typically recycle ideas from ballets they’d seen abroad, making their productions more or less copies of other people’s works. This was considered normal around the world, and choreographies could be credited either to the ballet masters or the original choreographers. In Finland, the situation came to a head at the start of the decade, when similarities were spotted between Elsa Sylvestersson’s Carmen and a previous interpretation by Roland Petit.

During the first decades of the Finnish Opera Ballet, the dancers’ facilities at the old Opera House were very modest. Rehearsals were conducted in the basement and in the attic, where lifts could only be practiced underneath a hole in the ceiling in the middle of the room. As there were no proper dressing or shower rooms, three dancers had to share a washbasin and a jug to wash after the performance. The situation improved dramatically in the 1950s with the completion of an annex to the Opera House on Bulevardi. It had a high-ceilinged rehearsal hall and six shower rooms with hot water.

Text JUSSI ILTANEN

Photos THE ARCHIVES OF THE FINNISH NATIONAL OPERA AND BALLET (for example P. Poutiainen, Tenhovaara, Waldemar Baronin, Taisto Tuomi)

Further reading

Laakkonen et. al. (edit.): Se alkoi joutsenesta. Sata vuotta arkea ja unelmia Kansallisbaletissa (Karisto 2021)

Suomen Kansallisbaletti 90 (Suomen kansallisbaletti 2012)

Irma Vienola-Lindfors & Raoul af Hällström: Suomen Kansallisbaletti 1922–1972 (Fazer 1981)

Pictures of performances and dancers from 1921 to 1962

Watch on Yle Areena

Watch on Elonet

Recommended for you

The Finnish Opera establishes a ballet company

Tours for soldiers and sad news from the front

Summer tours and films bring ballet to the entire nation

International stars from the east and west

Ballet masters change, Sylvestersson remains

The Finnish National Ballet as an ambassador for Finland

From a private ballet academy to professional education